Migration from Venezuela:

opportunities for Latin

America and the Caribbean

Regional socio-economic

integration strategy

Migration from Venezuela:

opportunities for Latin

America and the Caribbean

Regional socio-economic

integration strategy

Copyright © International Labour Organization & United Nations Development Programme, 2021

First published 2021

Publications of the International Labour Ofce and the United Nations Development Programme enjoy

copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may

be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or

translation, application should be made to ILO Publishing (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Ofce,

CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Ofce welcomes such

applications.

Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in

accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to nd the reproduction rights

organization in your country.

ILO-UNDP Data Catalog

Migration from Venezuela - opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean: Regional socio-economic

integration strategy. International Labour Organization & United Nations Development Programme, 2021, 68 p.

Labour migration, decent work, employment promotion, informal economy, social protection, Latin America.

ISBN: 978-92-2-034294-7 (print version)

ISBN: 978-92-2-034295-4 (web pdf)

Also available in Spanish:

Migración desde Venezuela: oportunidades para América Latina y el Caribe - Estrategia regional de integración

socioeconómica, ISBN: 978-92-2-033101-9 (print version); ISBN: 978-92-2-033100-2 (web pdf)

The designations employed in ILO and UNDP publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice,

and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of

the International Labour Ofce and the United Nations Development Programme concerning the legal status of

any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.

The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with

their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Ofce of the

opinions expressed in them.

Reference to names of rms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the

International Labour Ofce, and any failure to mention a particular rm, commercial product or process is not a

sign of disapproval.

This document was authored by Adriana Hidalgo and Francesco Carella from ILO, and David Khoudour from

UNDP.

February 2021

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is

mandated to promote decent work for all people

regardless of their nationality. The United Nations

Development Program (UNDP) works with people at

all levels of society to help create nations that can

cope with crises, and lead and sustain the kind of

growth that improves the quality of life of each and

every person. Both organizations joined forces to

develop this Regional strategy for socio-economic

integration.

1 The Regional Platform for Interagency Coordination was formed at the request of the Secretary General of the United Nations on April 12,

2018 to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM ) in order to

direct and coordinate the response of the system’s agencies to Venezuelan refugees and migrants, and to complement and strengthen

the countries’ national and regional actions. This response includes meeting the need for protection, assistance and integration of this

population in the host countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. At present, it is made up of international cooperation agencies,

non-governmental organizations, donor agencies and nancial institutions. The Regional Platform is replicated at the national level

through local coordination mechanisms established with the governments.

The Regional strategy was enriched by the

contributions of the agencies that are part of the

Integration Sector of the Coordination Platform for

Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V

1

) in an

effort to build coherent and complementary proposals

for efforts directed at the migrant population from

Venezuela, including refugees, asylum seekers and

returnees, as well as host communities in the region.

The strategy also contributes to the achievement of

the objectives of the Quito Declaration on Human

Mobility and Venezuelan Citizens in the Region, of

September 2018.

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

5

Context

Since 2015, more than 5.4 million people have had

to leave their country as a result of the economic,

social and political crisis facing Venezuela. Around

85% went to another country in Latin America and

the Caribbean (LAC). This gure, which does not

include hundreds of thousands of returnees, makes

this the most serious migration crisis in the history

of the region.

Often, destination countries view refugees and

migrants as a burden that affects the provision of

public services and the national and local scal

balance. However, international experience shows

that migrants, including refugees, also contribute to

the development of host countries (OECD-ILO, 2018).

Turning migration into a factor for sustainable

development requires that public authorities at

both the local and national levels promote the

socioeconomic integration of the refugee and

migrant population.

Why a Regional Strategy for

socio-economic integration?

While humanitarian aid seeks to meet the basic needs

of the refugee and migrant population, in particular

food, health and housing, a regional economic

integration strategy aims to make its recipients the

promoters of their own subsistence by promoting

their sustainable inclusion in host communities and

their contribution to local economies.

Who is it for?

The Regional Strategy is aimed at the main host

countries for the refugee and migrant population

from Venezuela; in particular, to government

institutions that have some degree of competence in

the socioeconomic integration of this population, and

to employers’ and workers’ organizations, with the

aim of promoting social dialogue around this area.

The countries participating in the Quito Process

identied socioeconomic integration as one of the

priority axes of their work agenda. In addition, the

Regional Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants

from Venezuela (RMRP, 2020), designed within the

framework of the Coordination Platform for Refugees

and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V), includes

socioeconomic and cultural integration among its

four axes for priority action.

Objectives of the Regional

Strategy

The Regional Strategy is oriented towards the

formulation of concrete responses to meet three

objectives:

1. To reduce the levels of socioeconomic vulnerability

of refugees and other migrants from Venezuela.

2. To maximize the contribution of this population to

the economies of the recipient countries.

3. To promote social cohesion through initiatives

that also benet the host communities.

Executive Summary

6

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Priority axes of the Regional

Strategy

The Regional Strategy is part of a medium and

long-term framework because it recognizes that the

majority of refugees and migrants from Venezuela

will settle for several years and that the only viable

option for them to contribute to the sustainable

development of their host countries is to promote

socioeconomic integration and coexistence with

their citizens. It is based on international standards

on labour and human rights.

To this end, the Strategy is articulated around seven

priority axes:

i. Regularization and proling of the population

from Venezuela: proposes making more flexible

and expediting the processes of regularization and

proling of the migrant and returned population

and carrying out studies on their demographic

and socioeconomic prole.

ii. Professional training and recognition of

qualications and competencies: seeks to

promote professional training and recognition of

qualications in the region in order to promote

labour inclusion.

iii. Employment promotion: plans to promote

access and efciency of labour intermediation

programs and platforms, boost the employability

of refugees and migrants, and adopt measures

for their transition into the formal economy.

iv. Entrepreneurship and business development:

includes the integration of migrants and refugees

into sustainable entrepreneurship programs

and value chains, as well as promoting self-

employment.

v. Financial inclusion: proposes facilitating access

to nancial services in host countries, promoting

nancial education and adapting banking

services to the needs of the migrant and refugee

population.

vi. Access to social protection, proposes the

preparation of a roadmap to promote a regional

social protection floor and a campaign to

disseminate information on access to social

security.

vii. Social cohesion: foresees the design of

institutional strengthening programs and

awareness campaigns to combat discrimination

and xenophobia.

Strengthening regional

cooperation mechanisms in

matters of the socio-economic

integration of refugees and

migrants into their host

communities

Until now, the Latin American and Caribbean

governments’ response to the Venezuelan migration

crisis has been directed more towards national action

than regional action, although the Quito Process

pursues the latter. For this reason, it is essential that

the countries of the region manage to strengthen

cooperation mechanisms and adopt and implement

truly regional policies, particularly in matters of socio-

economic integration for the refugee and migrant

population that comes from Venezuela, as well as for

host communities.

For the successful implementation of the seven

axes outlined above, it is key that the countries of

the region manage to strengthen their cooperation

mechanisms and adopt regional policies. The

Regional Strategy suggests how to develop and

implement such regional initiatives, focusing on the

areas of:

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

7

i. Human mobility and regularization: better

cooperation in the management of migratory

flows at the regional level and the adoption of

concerted regularization mechanisms to facilitate

intra-regional human mobility and socioeconomic

integration.

ii. Mutual recognition of degrees and

competencies: when a person, whatever their

nationality or immigration status, validates

a technical or academic degree in one of the

countries of the region or certies their labour

competencies, this recognition will be valid in the

other countries of the region.

iii. Labour intermediation: regional cooperation on

labour intermediation implies that both databases

of job vacancies in each country and those of the

job-seeking population, including refugees and

migrants, are shared.

iv. Social protection: the extension of subregional

agreements and promotion of coordination

between national social security laws to guarantee

the access of migrant workers and their families to

national social protection systems and reinforce

the system of portability of rights.

This type of initiative will contribute to a better

response to the protection and inclusion needs of

refugees and migrants from Venezuela at the regional

level in a context aggravated by the COVID-19 crisis.

It will also contribute to the achievement of the

objectives of the Quito Process.

8

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Executive Summary

Abbreviations Table

Foreword

Acknowledgments

1. Description

2. Objectives of the Regional Strategy for socio-economic integration

2.1 Why a Regional Strategy for socio-economic integration?

2.2 Applicability and relevance of a Regional Strategy

2.3 Who is the Regional Strategy for and what is expected after its implementation?

2.4 The norms and principles that support and guide the Regional Strategy

a. Technical and declarative instruments

b. Normative instruments of the United Nations System

c. Normative instruments of the Interamerican System for Human Rights

d. Normative instruments of the ILO

3. Socio-labour proling of the population from Venezuela

3.1 Main obstacles to labour insertion

3.2 Distribution and differences by gender

3.3 Main obstacles to labour insertion

3.4 Lack of decent work and job precariousness

3.5 Impact on employment and work due to the measures adopted to stop the spread of

COVID-19

3.6 Social protection in the regional context

4. Priority axes of the regional strategy for socioeconomic integration

4.1 Regularization and proling of the population from Venezuela

4.2 Professional training and recognition of degrees and skills

4.3 Promotion of employment

4.4 Entrepreneurship and business development

4.5 Financial inclusion

4.6 Access to social protection

4.7 Social cohesion

5. Strengthen regional cooperation mechanisms on socio-economic integration

5.1 Expand spaces for collaboration in areas of human mobility and regularization

5.2 Build a regional framework for the mutual recognition of degrees and skills

5.3 Promote labour intermediation at the regional level

5.4 Adopt regional social protection mechanisms

References

Graphics Index

Graphic 1. Percentage of Venezuelans and nationals in the informal sector

Graphic 2. Main areas of regional cooperation in socio-economic integration

Table Index

Table 1. Multilateral mechanisms in the region

Table of Contents

5

9

10

12

14

16

16

17

19

19

20

20

20

20

24

24

25

26

27

29

31

34

34

37

40

44

46

48

51

55

55

57

58

59

61

28

55

18

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

9

Abbreviations Table

LAC Latin America and the Caribbean

ACN Andean Community of Nations

CARICOM Caribbean Community

DTM Displacement Tracking Matrix

OECS Organization of Eastern Caribbean States

OISS Organización Iberoamericana de Seguridad SociaI (Iberoamerican Social Security Organization)

ILO International Labour Organization

IOM International Organization for Migration

PEP Special Residency Permit (Permiso Especial de Permanencia)

PEPFF Permiso Especial de Permanencia para el Fomento de la Formalización (Special Stay Permits

for the Promotion of Formalization)

PTP Permiso Temporal de Permanencia (Temporary Residence Permit)

UNDP United Nations Development Program (UNDP)

RPL Reconocimiento de aprendizajes previos (Recognition of prior learning)

RAMV Registro Administrativo de Migrantes Venezolanos (Administrative Registry of Venezuelan

Migrants)

RMRP Plan Regional de Respuesta para las Personas Refugiadas y Migrantes de Venezuela (Regional

Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela)

SICA Sistema de Integración Centroamericano (Central American Integration System)

10

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Foreword

The Latin American and Caribbean region today faces

some of the most acute crises in its history. In order

to face the health crisis and contain the spread of the

COVID-19 pandemic, most governments in the region

have adopted measures for physical distancing and

the restriction of mobility. These have resulted in a

protection crisis for the most vulnerable populations,

particularly those in situations of migration and forced

displacement, as well as a socioeconomic crisis that

has affected people employed in the most vulnerable

sectors of the economy, especially women.

These human development crises were added to

the migration crisis that has plagued the region for

half a decade as a result of the economic, social and

political situation in Venezuela. With more than ve

million Venezuelan refugees and migrants in the

world, around 85% of which are in Latin America and

the Caribbean, the region has to face new challenges

in terms of the mobility of people, access to basic

and protection services, inclusion in labour markets

and social cohesion.

Beyond the humanitarian response aimed at the

population from Venezuela and the host communities,

it is essential that the main recipient countries in the

region consider options to promote socioeconomic

integration and social cohesion. The document

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin

America and the Caribbean - Regional strategy for

socioeconomic integration seeks to respond to the

increasingly pressing challenge posed by the issue of

migration from Venezuela, particularly in the context

of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prepared jointly by the International Labour

Organization (ILO) and the United Nations

Development Program (UNDP), within the dual

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

11

framework of the Quito Process and the Coordination

Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela

(R4V), this document was enriched with inputs from

employers ‘and workers’ organizations, as well as

from the bodies that make up the R4V Integration

Sector. The document Migration from Venezuela:

opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean -

Regional strategy for socio-economic integration is

structured around seven priority axes: (i) regularization

and proling of the population from Venezuela; (ii)

professional training and recognition of degrees and

skills; (iii) job promotion; (iv) entrepreneurship and

business development; (v) nancial inclusion; (vi)

access to social protection; and (vii) social cohesion.

Since these efforts need to be part of a logic of

cooperation, the Regional Strategy proposes the

adoption of concerted mechanisms to facilitate

regional mobility and regularization of the population

in an irregular situation to promote the mutual

recognition of degrees and skills, develop initiatives

that improve labour intermediation at the regional

level, guarantee the access of refugees and migrants

to social protection systems and reinforce the

portability of acquired rights.

The unprecedented challenges faced by our region

require a coordinated response to build more

peaceful, just and inclusive societies, with decent

work, that take into account not only the needs and

vulnerabilities of refugees and migrants, but also

their contributions to the sustainable development of

the region. With this objective, our two organizations

are ready to support regional bodies as well as

national and local authorities in Latin America and

the Caribbean in the implementation of the measures

developed within the framework of this Regional

Strategy.

Vinícius Carvalho Pinheiro

Assistant Director-General of the ILO

Regional Director for

Latin America and the Caribbean International

Labour Organization

Luis Felipe Lopez-Calva

Sub-Secretary-General of the UN

Regional Director for

Latin America and the Caribbean United Nations

Development Programme

12

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

This Regional Strategy is the result of a collaboration

between the International Labour Organization (ILO),

the United Nations Development Program (UNDP),

the different agencies that make up the Coordination

Platform for Migrants and Refugees from Venezuela

(R4V) and the member countries of the Quito Process.

The document was drafted by Adriana Hidalgo and

Francesco Carella from the ILO and David Khoudour

from UNDP, under the direction of Vinícius Carvalho

Pinheiro, ILO Regional Director for Latin America and

the Caribbean, José Cruz-Osorio, Director the UNDP

Regional Centre for Latin America and the Caribbean,

and Jairo Acuña-Alfaro, Leader of the Governance

Team of the same Regional Centre.

The document also beneted from the valuable

contributions of the members of the R4V Platform,

led by the UNHCR and IOM, and especially those

partners that make up the Integration Sector.

Likewise, the support of the member countries

of the Quito Process was of great importance, in

particular the pro témpore Presidencies of Colombia,

Peru and Chile, as well as the representatives of the

organizations of workers and employers of the region,

who contributed signicantly to the development of

this document.

Finally, it is important to highlight the collaboration

and contributions of the participants of the different

spaces where this Regional Strategy was socialised,

among which the Technical Seminar with the

Integration Sector of the R4V Platform held on May

19, 2020, stands out, along with the Workshop on

Socio-economic Integration and follow-up to the

Recommendations of the Meeting of Ministers of

Labour of the Quito Process, held on August 20, 2020.

Acknowledgments

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

13

1

Description

The current Venezuelan migration crisis is the worst ever seen in the history

of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Since 2015, more than 5.4 million

Venezuelans have had to leave their country as a result of the economic,

social and political crisis facing Venezuela. This gure, which does not include

hundreds of thousands of returnees, makes it the second largest migration

crisis in the modern world, after the Syrian crisis.

14

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

About 85% of Venezuelan refugees and migrants

moved to another country in the LAC region.

Colombia is the country that is receiving the highest

numbers of people. As of August 5, 2020, this

country welcomed 1.8 million Venezuelans (35.8%

of the entire Venezuelan population in a situation of

mobility), as well as an estimated number of at least

500,000 Colombian returnees from Venezuela. They

are followed by Peru (830 thousand people), Chile

(455 thousand) and Ecuador (363 thousand). Brazil

(265 thousand) is the sixth largest recipient country

for the Venezuelan population, just after the United

States (351 thousand) and before Argentina (179

thousand) (R4V, 2020).

For their part, Aruba (16%), Curaçao (10.1%),

Colombia (3.6%), Panama (2.9%) and Guyana (2.8%)

are the main recipient countries as a percentage of

the host population. This implies that these countries

are the ones with the greatest pressure in terms

of humanitarian assistance, provision of public

services, access to jobs and citizen coexistence. In

other countries in the region, such as Brazil, Mexico

and Paraguay, the Venezuelan population represents

only 0.1% of the total. Their absorption capacities are

higher, while the costs associated with the integration

of the Venezuelan population are lower than those

of host countries with a higher concentration of

Venezuelan population.

In the region, many destination countries tend to view

refugees and migrants from Venezuela as a burden

that affects the provision of public services and the

national and local scal balance, not to mention

the challenges in terms of cohesion and peaceful

coexistence. However, international experience

shows that immigrants, including refugees, also

contribute to the development of their host countries

(OECD-ILO, 2018). On the one hand, they represent

a source of human capital that makes it possible to

respond to the labour shortage in some sectors of

the economy. They also invest and consume, which

2 “A economía de Roraima e o fluxo venezuelano”. Fundação Getulio Vargas - Diretoria de Análise de Políticas Públicas (FGV-DAPP),

ACNUR, Observatório das Migrações Internacionais (OBMigra), Universidade Federal de Roraima (UFRR) y ACNUR.

contributes to feeding aggregate demand and thus

GDP growth. On the other hand, by paying taxes,

directly and indirectly, the refugee and migrant

population contributes to improving the scal

balance of their host countries.

An example of the positive effects on the local

economy was evidenced in a study on the impact

on society and the economy of the arrival of

Venezuelans to Roraima, Brazil. This municipality

registered growth and economic diversication

during the period of highest influx

2

. Likewise, the

tax receipts generated in 2018 by all Venezuelans is

comparable to the additional expenses required for

their acceptance, with both gures in the range of R

$ 100 million.

Turning migration into a factor for sustainable

development requires that public authorities,

both at the local and national levels, promote the

socioeconomic integration of the refugee and

migrant population. This is precisely the purpose of

this Regional Strategy. The health, economic and

social crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic

makes it an even more necessary tool.

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

15

2

Objectives of the

Regional Strategy

for socio-economic

integration

The Regional Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (RMRP,

2020) includes socio-economic and cultural integration among the priority

lines of action of the Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from

Venezuela (R4V). It also highlights the fact that “effective socio-economic

and cultural integration is favourable not only for refugees and migrants from

Venezuela, but also for host communities.”

16

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Likewise, within the framework of the Meeting of

Ministries of Labour in support of the Quito Process,

in Bogotá, Colombia (November 13, 2019), the

representatives of different Ministries of Labour

of Latin America and international cooperation

organizations insisted on the need to “promote

socio-economic integration with an emphasis on

access to the labour market for refugees, migrants

and returnees from Venezuela in Latin America and

the Caribbean through collaborative work with the

different international cooperation organizations and

agencies within the decent work framework. ” They

also recommended “cooperating with the design of

an income generation strategy for refugees, migrants

and returnees from Venezuela, linked to migration

policies, which contributes to the formalization of

work and progressive access to a social protection

floor.”

The Regional Strategy for Socio-economic Integration

constitutes a concrete response to this dual concern of

the Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants

from Venezuela and of the Ministries of Labour of the

member countries of the Quito Process. Not only is

it part of a humanitarian logic of reducing the levels

of socioeconomic vulnerability of refugees and other

migrants who come from Venezuela, but it also seeks

to maximize the contribution of this population to the

economies of the recipient countries and promote

social cohesion through initiatives that also benet

the host communities.

2.1 Why a Regional Strategy

for socio-economic

integration?

While humanitarian aid seeks to satisfy the basic

needs of the refugee and migrant population, in

particular food, health and housing, an economic

integration strategy aims to support the recipients

in becoming actors of their own subsistence. In this

sense, it is a recognition that “there is a growing

need to strengthen the link between humanitarian

assistance and development in the global response

and to place employment in a strategic place

between both components” (ILO, p. 12, 2016). It also

responds to the need to develop or strengthen labour

market institutions and programs that support local

integration, resettlement, voluntary repatriation and

reintegration, as reafrmed in the ILO’s Guiding

Principles: Access of refugees and other forcibly

displaced persons to the labour market.

Refugees and migrants from Venezuela face a series

of obstacles that hinder their integration into the

region’s labour markets or prevent them from creating

their own businesses. The lack of a regular status

represents one of the biggest obstacles to getting

a formal job or starting a business. However, those

in a regular situation also have difculties accessing

decent jobs and obtaining recognition of their

academic degrees and professional skills. Accessing

opportunities to develop skills and competencies

that allow them to be more competitive in the

labour market represents an additional obstacle.

The population from Venezuela, including returnees,

also faces discrimination problems and a high risk

of labour exploitation. This situation is even more

acute in the case of vulnerable populations, such

as women, ethnic minorities and disabled people,

among others.

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

17

In this sense, the Regional Strategy describes the

main ways to promote socioeconomic integration

with special consideration for women, who face more

precarious labour insertion conditions and greater

risks of violence and sexual and labour harassment

for gender reasons, among other realities.

The health, socioeconomic and care crisis generated

by COVID-19, as well as the physical distancing

measures that have been taken throughout the

region, aggravated the migratory crisis and increased

the risks of rejection towards people from Venezuela.

Within the host communities, many people already

experienced situations of poverty, hunger and

exclusion. For this reason, promoting socioeconomic

integration implies thinking about sustainable

development strategies that consider the community

as a whole, and that can and should benet everyone.

A strategy that is exclusively oriented towards the

refugee and migrant population could contribute

to increasing the frustration of the local population

and represent a factor for rejection, especially in the

current context of COVID-19.

From this perspective, the Regional Strategy for

socioeconomic integration is structured around

seven axes:

1. Regularization and proling of the population

from Venezuela

2. Professional training and recognition of

qualications and skills

3. Job promotion

4. Entrepreneurship and business development

5. Financial inclusion

6. Access to social protection

7. Social cohesion

3 International Labour Organization. ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. See: https://www.ilo.org/declaration/

lang--es/index.htm

Each country will be able to position itself in relation

to this Regional Strategy based on its specic needs

and progress on the seven aforementioned axes,

but always within a framework of respect for human

rights and international labour standards, in particular

the fundamental principles and rights at work

3

. The

participation of the social partners (employers’ and

workers’ organizations) in a tripartite social dialogue

with the Government is very important to dene the

specic adaptations to guide this Strategy in each

national context.

2.2 Applicability and relevance

of a Regional Strategy

When targeting diverse countries, a Regional Strategy

poses the challenge of applicability, adaptability and

relevance. Among the challenges, these factors

should be recognized above all:

} The global socio-economic context derived from

the effects of the pandemic caused by COVID-19

and the quarantine and social distancing

measures adopted by each country.

} The different institutional capacities of each

country.

} That the countries are at different stages of

development to respond to the needs and

demands of the target population of this Regional

Strategy.

Faced with these divergences, an added value of

the regional proposal is to seek that the countries

give each other feedback through the exchange of

good practices and lessons learned. Membership in

regional mechanisms facilitates a more articulated

response (see Box 1).

18

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Regional collaboration within the Quito Process,

as well as the support of the different actors of the

Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants

from Venezuela (R4V), also constitutes an added

value for the successful implementation of the

Regional Strategy for socio-economic integration.

Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR)

●Multilateral Agreement on Social Security (1997).

Agreement on Residence for Nationals of MERCOSUR Member States and Agreement on Residence for Nationals

of MERCOSUR Member States, Bolivia and Chile.

Plan to Facilitate the Free Movement of Mercosur Workers (2013

Andean Community of Nations (ACN): Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru

Andean Instrument for Labour Migration (2003) - Participants: Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.

Andean Instrument for Labour Migration (Decision 545).

Resolution 957: Regulation of the Andean Instrument for Safety and Health at Work.

Pacic Alliance

Its creation, via the Declaration of Lima (2011), established the purpose of progressively advancing towards “the

free movement of goods, services, capital and people,” to prioritize “the movement of business people and facilitate

migratory transit including migratory cooperation and consular police.”

Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

●Members: Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica,

Monserrat, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and

Tobago.

Agreement on Social Security (2006).

Central American Integration System (SICA)

The Central American Social Integration Treaty (Treaty of San Salvador, 1995) aims to achieve Central American

social integration through the coordination, harmonization and convergence of national social policies, for which

purpose the Social Integration Subsystem was created and the Central American Social Integration Secretariat

(SISCA) was established.

Ibero-American Social Security Organization (OISS)

●Ibero-American Multilateral Agreement on Social Security.

Table 1. Multilateral mechanisms in the region

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

19

2.3 Who is the Regional

Strategy for and what

is expected after its

implementation?

The Regional Strategy is directed at the governments

of the main host countries for refugee and migrant

populations that come from Venezuela, especially

government institutions that have some degree of

competence in their socio-economic integration.

It draws on the Colombian experience, where the

Venezuelan Border Management of the Presidency of

the Republic, with the support of UNDP, designed an

income generation strategy for the migrant population

from Venezuela and the host communities (UNDP /

Presidency of the Republic of Colombia, 2019).

Following the implementation of the Strategy, the

population from Venezuela, as well as members of

the host communities, especially those affected by

the health, socioeconomic and care crisis induced by

COVID-19 are expected to:

} Benet from a regular immigration status that

allows them, among other things, to have access

to public or reasonably priced health services,

education, care and nancial services, as well as

to develop new skills and manage the recognition

of their degrees and skills, insert themselves into

the labour markets of the host countries and

create their own businesses.

} Have access to salaried jobs or under the

modality of self-employment in the formal sector

of the economy, with full exercise of their labour

rights and in observance of health and safety

regulations at work, as well as those referring to

the minimum age of admission to employment.

4 This guarantee of access to a minimum level of social protection must be articulated within the framework of a broader strategy of

extension of coverage through an integrated policy approach and access to higher levels of social protection in line with Convention No.

102 of the ILO on the minimum standard of social security.

} Benet from a social protection floor against a

state of need or social vulnerability that requires

the intervention of the different non-contributory

programs, to guarantee access to a basic level

of social protection. This floor will allow, as a

minimum, that they have access throughout

their life cycle to essential health care and basic

income security that, in turn, will enable them

to have effective access to goods and services

dened as necessary at the national level

4

.

2.4 The norms and principles

that support and guide the

Regional Strategy

The recommendations included in this document are

part of the global agenda on migration, particularly

labour, forced displacement and sustainable

development. They are based on the guiding principles

dened in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and

Regular Migration (UN, 2018a), the Global Compact

on Refugees (UN, 2018b) and the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development (UN, 2015). The Regional

Strategy follows the guiding principles of human

rights and a gender perspective and adopts a pan-

governmental and pan-social approach.

Likewise, there is a migration governance framework

at the international level that is made up of binding

and non-binding normative instruments, guiding

technical instruments for the denition of national

policies, and others that meet universal aspirations.

These are included in the basis of this Regional

Strategy, but it is also hoped that the countries that

have not ratied them - where appropriate - move

towards this process and that, in all cases, their

content is disclosed and implemented.

20

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Those that are most closely related to the dimensions

addressed by this strategy are listed below,

recognizing that the list can be much longer:

a. Technical and declarative instruments

ILO multilateral framework for labour migration.

Non-binding principles and guidelines for a

rights-based approach to labour migration

(2007).

High-Level Dialogue on International Migration

and Development (2013). General Assembly of

the United Nations.

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

(2015). General Assembly of the United

Nations.

The “Guiding principles on the access of

refugees and other forcibly displaced persons

to the labour market” (2016).

General principles and guidelines for fair

recruitment and Denition of recruitment fees

and related expenses (2016 and 2018).

Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular

Migration (2018).

Global Compact on Refugees (2018).

Declaration of Panama. 19th American

Regional Meeting of the ILO (2018).

ILO Centenary Declaration on the Future of

Work (2019). International Labour Conference,

One Hundred and Eighth Session to mark the

Centenary of the ILO.

Resolution on the ILO Centennial Declaration

on the Future of Work (adopted on June 21,

2019).

b. Normative instruments of the United

Nations System

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Discrimination against Women (1979).

General Assembly of the United Nations.

International Convention on the Protection

of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and

Members of Their Families, adopted by

the United Nations General Assembly in its

resolution 45/158, of December 18, 1990.

Convention on the Status of Refugees, adopted

on July 28, 1951 by the Plenipotentiary

Conference on the Status of Refugees and

Stateless Persons, convened by the General

Assembly of the United Nations.

Protocol on the Status of Refugees, signed

on January 31, 1967 at the United Nations

General Assembly.

c. Normative instruments of the Interamerican

System for Human Rights

Convention on Political Asylum (1933).

Inter-American Convention on the Prevention,

Punishment and Eradication of Violence

against Women or “Convention of Belem do

Pará” (1994).

Convention on Diplomatic Asylum (1954).

Convention on Territorial Asylum (1954).

Additional Protocol to the American Convention

on Human Rights in the area of Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights or “Protocol of San

Salvador” (1988).

Inter-American Convention Against all Forms

of Discrimination and Intolerance (2013).

d. Normative instruments of the ILO

The fundamental ILO conventions are listed, so

named because they are a prerequisite for the

development of subsequent governance conventions

and considered a priority due to their relevance to

the operation of the international labour standards

system. Other conventions and recommendations

that address the components of this strategy

(employment, social protection, rights of migrant

workers and development of human resources,

among others) are also considered.

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

21

d.1 Core conventions

Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29)

and its Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour

Convention, 1930.

Freedom of Association and Protection of the

Right to Organize Convention, 1948 (No. 87).

Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining

Convention, 1949 (No. 98).

Equal Remuneration Convention, 1951 (No.

100).

Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957

(No. 105).

Discrimination (Employment and Occupation)

Convention, 1958 (No. 111).

Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No. 138).

Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention,

1999 (No. 182).

d.2 (Priority) governance conventions of the ILO

Labour Inspection Convention, 1947 (No.

81); Protocol of 1995 relating to the Labour

Inspection Convention, 1947.

Employment Policy Convention, 1964 (No.

122).

Labour Inspection (Agriculture) Convention,

1969 (No. 129).

Tripartite Consultation (International Labour

Standards) Convention, 1976 (No. 144).

d.3 Other applicable ILO conventions and

recommendations

Conventions

Preservation of Migrants’ Pension Rights

Convention, 1935 (No. 48).

Employment Service Convention, 1948 (No.

88).

Migrant Workers Convention (Revised), 1949

(No. 97).

Social Security (Minimum Standards)

Convention, 1952 (No. 102).

Plantations Convention, 1958 (No. 110) and

its Protocol of 1982 relating to the Plantations

Convention, 1958.

Equality of Treatment (Social Security)

Convention, 1962 (No. 118).

Employment Injury Benets Convention, 1944

(No. 121).

Invalidity, Old-Age and Survivors’ Benets

Convention, 1967 (No. 128).

Medical Care and Sickness Benets

Convention, 1969 (No. 130).

Human Resources Development Convention,

1975 (No. 142).

Migrant Workers (Supplementary Provisions)

Convention, 1975 (No. 143).

Workers with Family Responsibilities

Convention, 1981 (No. 156)

Preservation of Social Security Rights

Convention, 1982 (No. 157).

Employment Promotion and Protection

against Unemployment Convention, 1988 (No.

168).

Private Employment Agencies Convention,

1997 (No. 181).

Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No.

183).

Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189).

Violence and Harassment Convention, 2019

(No. 190).

Recommendations

Livelihoods Security Recommendation, 1944

(No. 67).

Medical Care Recommendation, 1944 (No. 69).

Migrant Workers Recommendation (Revised),

1949 (No. 86).

Migrant Workers Recommendation, 1975 (No.

151).

Social Protection Floors Recommendation,

2012 (No. 202).

Transition from the Informal to the Formal

Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204).

Employment and Decent Work for Peace and

Resilience Recommendation, 2017 (No. 205).

Violence and Harassment Recommendation,

2019 (No. 206).

22

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

The Regional Strategy is established within this

regulatory framework and is based on the following

principles:

All of the actions implemented include both

the refugee and migrant population, including

returnees, as well as the host communities,

unless for some reason their application is

specied only for one or the other.

It is recognized that refugees enjoy a different

protection status under international law.

Respect for human rights in general and

labour rights in particular are guaranteed for

all working people in a situation of mobility.

Tripartite social dialogue is promoted in the

debate on and denition of the governance

frameworks for labour migration.

The actions for implementing the Strategy

include the promotion of decent work, both in

the urban and rural sectors.

The exercise of freedom of association

and collective bargaining is recognized and

guaranteed.

It is based on and promotes equal opportunities

and treatment in employment, as well as

respect for diversity.

The right of minors to live free from child

labour and hazardous work.

The right of people to live free from forced

labour.

The promotion of a national social protection

floor, which guarantees income security

throughout the entire life cycle and effective

access to essential health services,

accompanies measures to promote socio-

economic integration because this constitutes

one of the elements required for decent work.

It is formulated from a gender and

intersectional perspective that considers the

relevance of the service offer according to

the life cycle and the business cycle, which

guides actions and strategies, and recognizes

the different experiences faced by women in

terms of barriers to socioeconomic inclusion

and, in particular, those related to care needs

and responsibilities for families, which usually

falls on migrant women.

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

23

3

Socio-labour proling

of the population from

Venezuela

Socio-economic integration is essential for the population from Venezuela,

who need stable sources of income to sustain themselves in their new location

and send remittances to their families. However, despite the fact that the

majority of Venezuelans and returnees are of a productive age and have a high

educational prole, they face many challenges when entering the labour market

under decent working conditions.

24

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

3.1 Age and educational prole

According to various studies, the majority of refugees

and migrants from Venezuela are young, between 18

and 35 years old, with the group between 26 and 35

years old being the largest, followed by the group

of people between 18 and 25 years old. Salgado et

al. (2017) point out that in Chile, the population of

Venezuelans is young and in full productive capacity

because they belong to the age range of between 20

and 35 years old and, to a lesser extent, in the range

of 36 to 50 years, with an average of 29.2 years.

Similarly, Simoes, Cavalcanti, Moreira and Camargo

(2018) point out that in Brazil, Venezuelan immigrants

are mostly young (72% are between 20 and 39 years

old). Ramírez et al. (2019), and further establish that

in Ecuador, 55% of the Venezuelan population is in

the age range between 18 and 35 years.

An analysis of the most recent reports of the

IOM Displacement

5

Tracking Matrix (DTM) for

the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean

corroborates these results. In Panama, 83% of the

Venezuelan people surveyed are in the age range

of 18 to 45 years, with a higher concentration in the

ages of 26 to 35 years (DTM September 2019); in

Trinidad and Tobago, the majority are between 25

and 29 years old, followed by the group of people

between 30 and 34 years old (DTM September 2018).

The analysis of these same reports makes it possible

to verify that Venezuelans with higher educational

levels migrate to the Southern Cone of America,

Panama, Mexico, Costa Rica and the Dominican

Republic, while those with technical and secondary

educational proles (mostly complete) tend to migrate

to the Andean countries, Brazil and the Caribbean

countries of Aruba, Curaçao, Trinidad and Tobago,

5 The Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) is IOM’s global tool for capturing, processing and generating information on the movements

of people in different countries. Specically, they are surveys of people over 18 years old that are carried out at border points and

destination cities. They provide information on the prole of people in human mobility, transit routes, living and working conditions, as

well as the particular vulnerabilities and specic needs they face.

6 According to a report on the RV4 Platform, there were three shipwrecks that caused more than 80 deaths of Venezuelans who were

taking the sea route to Caribbean countries (RV4 April-May 2019).

and Guyana. This is presumed to happen because

those with a higher occupational qualication

migrate to countries that are perceived to have

better and greater job opportunities (Bravo and Úzua,

2018; Koechlin, Solórzano, Larco and Fernández-

Maldonado, 2019). It also follows that, due to their

socioeconomic prole, the rst group corresponds

to people with the ability to travel to more distant

destinations since, according to the DTM analysed,

those who migrate to the Southern Cone, Panama,

Mexico, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic

make all or part of the trip by plane while those who

travel to neighbouring or closer countries make part

of their trip by bus, boat

6

and / or on foot.

However, some differences between the rst and

second migratory waves can be identied. The

rst migrations corresponded mainly to people

with postgraduate, university and higher technical

studies, including professionals in careers such

as Engineering, Social Sciences, Administrative

Sciences, Education, Medicine and Law, among

others (Mercer, 2019; Tincopa et al., 2019; Salgado

et al., 2017). The most recent waves include younger

people with less education and little work experience.

In other words, recent migrations are of people who

leave the country in conditions of greater vulnerability

and with less work experience (Blouin, 2019).

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

25

3.2 Distribution and differences

by gender por género

Women represent about half of the people who

come from Venezuela and, on average, have higher

educational levels than their male counterparts;

they also have work experience. It is estimated that

more than 70% worked before migrating and of

these, approximately 57% had a formal job, a similar

proportion to their male counterparts, while 16% were

unemployed (9% of men were) ( IOM, 2018).

Despite this, they face signicantly worse job

placement conditions than men. Unemployment

is generally double what they experienced before

they migrated and at least double that of their male

counterparts. These results are influenced by the

combination of the sexual division of labour within

households and in labour markets, and the violence

experienced in transit and destination (Carcedo,

Chaves Groh and Larraitz Lexartza, 2020).

Within households, the migratory experience tends

to reinforce, reproduce and increase the differences

in the distribution of care work and other unpaid

tasks. Women who come from Venezuela take care

of the family more intensively than before migrating

and do so more than men. This difference tends

to grow in the places of destination, where the

difculties of educating the little ones, the lack of

care services and support networks, and the scarcity

of resources that prevent hiring third parties for

household tasks lead women to disproportionately

assume reproductive responsibilities within families.

To meet this demand, they also do not have the

help of the extended family and, in particular, of

older women; less than 10% of women are over

50 years old. For women heads of households,

the pressure is even greater (Carcedo et al., 2020).

In LAC countries, the sexual division of labour outside

the home produces labour markets with strong

segmentation and horizontal segregation by sex, which

implies a high concentration of women in professions

and trades that require fewer qualications (ECLAC,

2019). These markets favour the disqualication of

women who come from Venezuela and reinforce

precarious work in jobs that are usually located within

the informal economy and, therefore, in working

conditions with a lack of decent work. Among

these are occupations related to cleaning, caring

for other people, and street vending. In fact, women

reach a labour market that is already segregated

by sex, but they only manage to insert themselves

into feminized and low-productivity occupations.

They are not successful in entering occupations

where women are the majority, but require high or

medium-high qualications, such as health and

education. For many, this segmentation of the labour

market implies giving up their professions and work

experiences and reinforces their disproportionate

participation in the care economy in two ways:

inside and outside their homes, paid and unpaid.

The violence and harassment experienced by women

and girls of all ages who come from Venezuela also

impact their access to livelihoods and contribute to

their exclusion from labour markets, which implies

loss of employment, lack of incentive to search and

consequent real access only to jobs with high levels

of risk. Street sales, domestic work and sex work are

some of the sectors in which migrant women nd

employment opportunities and, at the same time,

risk situations, as well as exposure to violence and

exploitation.

The reinforcement of the domesticity mandate

reaches not only the loss of their professions,

businesses or disconnection from the collective

spaces in which they were reafrmed, they also lose

the possibility of acting and interacting on their own

behalf in different settings and with different people.

This drastic change, the lack of job opportunities and

precarious living conditions, as well as an increase in

reproductive workloads and the risks of sexual, sexist

and xenophobic violence reinforce this enormous

decline in their quality of life.

26

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

3.3 Main obstacles to labour

insertion

In general, refugees and migrants from Venezuela,

especially women, nd more opportunities to

be employed in the informal economy, with the

limitations it implies in terms of access to labour

rights. The reason is structural: between half and

three-quarters of the jobs in Latin America and

the Caribbean are in the informal economy, either

because they are jobs without a formal contract and

in precarious conditions or because they include low-

productivity enterprises and, therefore, do not offer

the possibility of affording coverage against various

risks of the present and future (ILO, 2019).

In Peru, the study by Koechlin et al. (2019) points

out that the insertion of Venezuelan people into

employment “has been at the cost of reinforcing

the predominant tendencies of the Peruvian

occupational structure, that is, the generation of

employment in the informal sector of the economy”

(2019, pp. 50 -51). In its study on immigration of

South Americans in Argentina, the ILO (2011, p. 123)

indicates that these people are inserted in “(…) a

labour market characterized by the high presence of

precarious jobs for the population as a whole, where

the migrant population takes the worst part (…). ” The

insertion of the migrant population into the labour

market is determined, therefore, by its structure and,

in this case, by informality, clearly to the detriment

of compliance with labour rights. In Trinidad and

Tobago, more than 90% of Venezuelans surveyed for

7 The delays in obtaining an appointment to start the application for the residency procedure in Argentina are up to 12 months. On the

other hand, in May 2018, the Argentine Executive increased the prices of all administrative immigration fees, including the fee to request

an urgent appointment that increased ve times from 2,000 to 10,000 Argentine pesos (from 47 to 234 euros) (Pacecca, 2018, in Acosta

et al., 2019).

8 In Panama, among the different challenges to regularizing or applying for refugee status, the DTM report indicates: (1) the expiration

/ theft / loss of passport (Venezuelan people are not accessing new documents either in the consulates or in Venezuela) although,

on occasions, they receive consular certicates of passport extension for the immigration and labour regularization procedures; (2)

the cost of immigration regularization and legal representation. Additional costs include the processing and sending of documents to

Venezuela, payment to the responsible person in Panama and travel / stay in the capital for those who live in the interior of the country

(DTM September 2019, p. 15).

9 In Ecuador, where neither documents nor extenuating circumstances are required, the main limiting factor to obtaining documentation

is the cost. The visa application costs 50 USD; the UNASUR Visa costs 250 USD, and the temporary visa costs 400 USD (Ministry of

Foreign Relations, 2019, in Célleri, 2010, p. 13).

the DTM report indicated that they were working in

the informal sector (DTM September 2018).

In relation to immigration regulation, the processes

involved are long and expensive, and in some cases

access to it is impossible. Not having a regular

immigration status constitutes a limitation for access

to decent work, as already outlined by various studies

(Tincopa, 2019

7

; Acosta et al., 2019

8

; DTM Panama

2019; Célleri, 2019

9

). In the Dominican Republic, the

DTM report indicates that, “although the Venezuelan

population nds activities that generate income,

these are low. There is limited access to labour rights

due to their irregular migration status ”(DTM October-

November 2018). In a study carried out with women

in Peru, the results of which can be extrapolated

to men, the following were identied as obstacles

to labour insertion: (1) the difculty of requesting

appointments at the National Directorate of Migration,

which leads women to resort to “processors” (people

who can access the website at dawn to process an

appointment); (2) the existence of few State ofces

for managing immigration documents, such that

women have to stand in long lines to obtain them;

and (3) high costs, such as for the Interpol File and

the immigration card (Tincopa, 2019).

Having a document proving one’s refugee status or

a work permit is not a guarantee of access to the

job market. There are some barriers that are related

to the lack of information on the part of the private

sector about this migratory category, since they

do not know whether these documents are valid

and are not sure of the existence of restrictions to

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

27

hiring migrants, such as work permits for certain

occupations.

Access to vocational training in the LAC region is

usually conditioned on the possession of immigration

documentation and, in general, a residence card and

a basic level of education are required according

to the policies of vocational training institutes.

Sometimes, as previously mentioned, migrants and

refugees do not carry their diplomas and, therefore, it

is impossible to demonstrate the minimum required

degree, which makes it impossible to access these

alternatives to strengthen employability. In countries

like Costa Rica, people between the ages of 15 and

17 can access the courses available at the Instituto

Nacional de Aprendizaje (INA), regardless of their

immigration status. Access facilities for this type

of training promote job placement under more

favourable conditions, because they allow access to

degrees that prove mastery of certain skills.

The validation of university degrees requires going

through tedious processes (obtaining apostilles

or nding documents that are not available in

Venezuela), that are long and expensive. In many

cases, the document that they do not carry or that

they cannot obtain is the diploma itself: “despite the

fact that 40% of the Venezuelan people surveyed

have higher education, only half have been able to

bring their diploma to Peru (50 %). Of this group, only

half have validated their diploma (50%) ”(Blouin, 2019,

p. 58). A related problem is the inability to obtain

documents in Venezuela when requested.

The costs also represent an obstacle because “the

Venezuelan migrant must debate whether to assume

the costs of validating professional degrees or

whether to save that money for survival purposes or

for sending remittances” (Blouin, 2019, p.59). This

situation generates a low correspondence between

their studies (university or technical-superior) and

the type of work they perform.

Koechlin et al. (2019), in their study on labour

insertion in Peru, asked what is the relationship

between the training that the Venezuelan migrant

brings and the occupation they perform: of 575

people who completed their university or technical

degree studies, only 7,65% are working in their eld

of study (university students and technicians in their

profession), while 92.35% are working in some other

activity. Among those surveyed, inappropriateness

affects both men and women in a similar proportion.

It should be taken into account that, sometimes,

countries limit the incorporation of workers to certain

occupations or professions, so this inappropriateness

is not always due to barriers related to the recognition

of degrees.

3.4 Lack of decent work and job

precariousness

The majority of Venezuelan migrants and refugees,

regardless of their educational level and work

experience, are working in the informal sector.

The most frequent occupations are: in shops,

street vendors, customer service, restaurants and

construction; a majority of women are relegated

to paid care and domestic work. Informal working

conditions do not meet the requirements of labour

legislation. They are characterized, on the contrary, by

the lack of a written employment contract, existence

of longer or shorter working hours than desired,

payment of minimum wage or less, non-payment

of wages, lack of social protection (they do not have

access to health or pension systems), disrespect

for labour rights (bonus, vacation pay and overtime,

among others) and early dismissals after passing the

trial period.

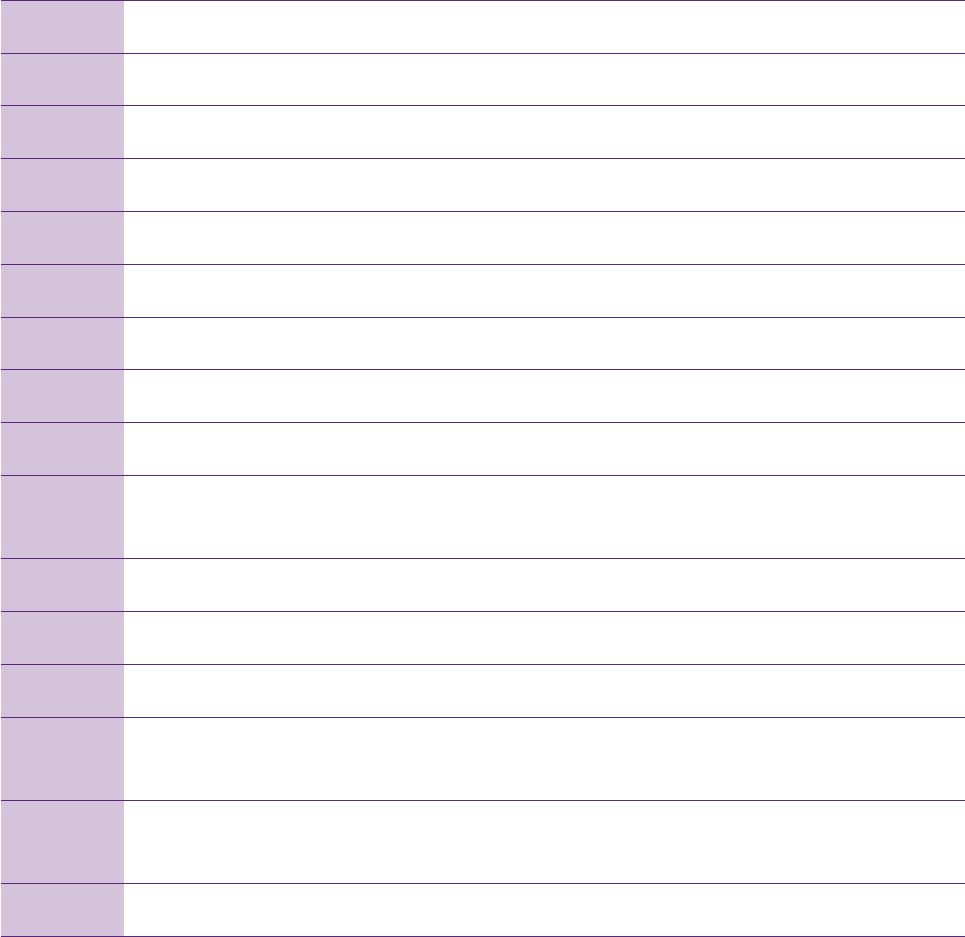

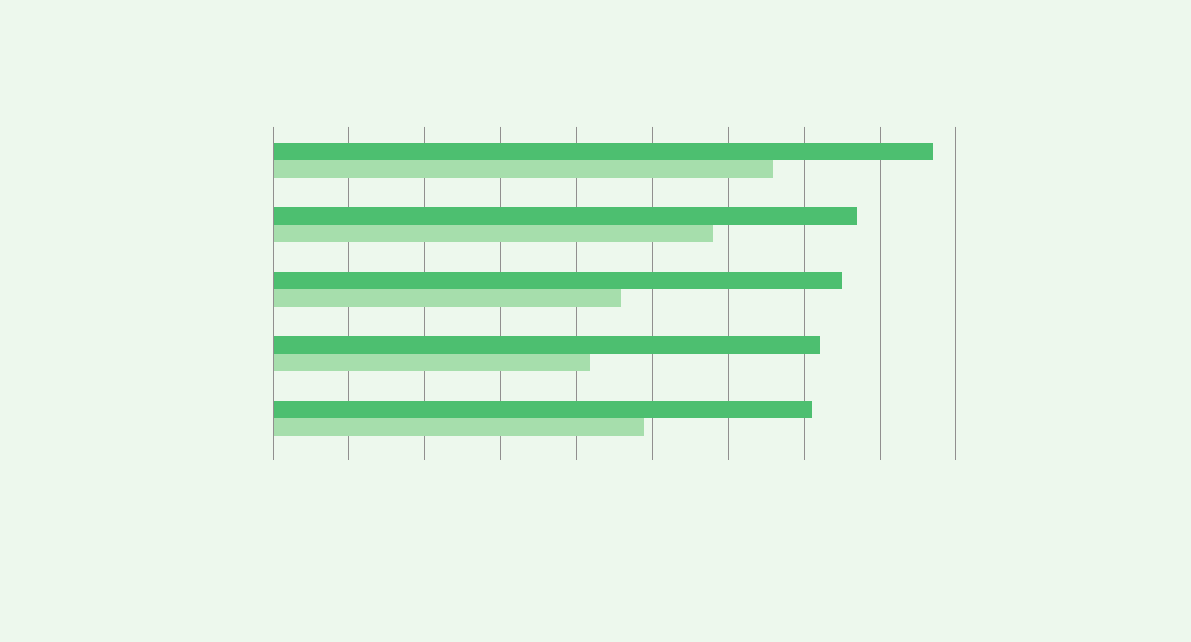

Figure 1 compares the percentages of informal

work among nationals and people of Venezuelan

origin in ve South American countries: Argentina,

28

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. The percentage

of Venezuelans working in the informal sector is

systematically higher than that of nationals and

exceeds 70% in all ve countries. On average, the gap

between the two populations is around 24%.

Graphic 1. Percentage of Venezuelans and nationals in the informal sector, 2018-19

Perú

Colombia

Ecuador

Brasil

Argentina

0 2010

% of Venezuelans working in the informal sector

% of nationals working in the informal sector

30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Source: World Bank (2020).

In Chile, Salgado et al. (2017) report that 45% of the

Venezuelan people surveyed in their study entered

the labour market as salespeople and that another

20% are working as waiters, which is equivalent to

saying that 65% work in the service sector, under the

modality of customer service. In Peru, Tincopa et al.

(2019) point out that 29% of women who work do so

in itinerant or informal jobs and 43% in jobs related

to direct sales or customer service. Thus, “a very

notable characteristic of the Venezuelan migrant

population in all the countries of South America,

including Ecuador, is their presence in the streets,

squares, parks and markets, selling products such as

sweets, fast food, homemade sweets, juices, or the

traditional Venezuelan arepa ”(Ramírez et al., 2019,

p. 20).

Koechlin et al. (2019) note that a visible characteristic

of the labour insertion process consists of “the

precarious working conditions in which a signicant

percentage of immigrants nd themselves. (…) The

precarious factors are reflected in the working hours,

salaries, formality and informality of employment,

job rotation ”(p. 36). The study shows that, for

Lima, Arequipa and Piura, 82% of the Venezuelan

people surveyed reported working longer than the

established legal workday, which is equivalent to 48

Regional socio-economic integration strategy

29

hours per week

10

and 46% reported having an income

below the minimum wage. When introducing the

gender variable, the study nds that more Venezuelan

women receive an income below the minimum

compared to their male peers (58% reported by

women versus 37% reported by men).

For Chile, Salgado et al. (2017) point out that although

49% of the people surveyed had a written contract,

“some 43.1% of those who have a contract, do not

contribute to the pension fund. This situation has a

certain correlation to when they were asked if they

were contributing to the health system (…), 17.4% of

those who have some type of employment contract

do not contribute to the health system ”(p.108). Célleri

(2019), in the study on Ecuador, found that 51% of

the people surveyed with a job have a dependency

relationship, but 70% indicate that they have not

signed a contract. According to the author, a possible

explanation for this situation is that they enter jobs

under the condition of a “probationary period,” which

according to current legislation in Ecuador is three

months, a period in which employers can make

dismissals without the obligations that they would

have under a xed contract and with the payment of

social security.

This situation is also evident in the DTM reports.

In Brazil, 80% of the people who reported being

employed receive less than the minimum wage and

72% did not sign any employment contract (DTM

April 2019). In Paraguay, 20% of the people who

reported employment earn less than the minimum

wage (DTM October 2018). In Trinidad and Tobago,

47% of Venezuelan people who work reported earning

less than the minimum wage and 23% reported

being in violation of their labour rights for not being

paid or being paid less than the agreed salary (DTM

September 2018).

10 When cross-analyzing the variables of working hours and remuneration, the study found no relationship between greater number of

hours worked and higher remuneration.

Women also face the worst working conditions in

the informal sector; more often they lack a contract,

earn less than the minimum and less than their male

counterparts (wage gap), and work fewer hours than

desired. They also face particular risk situations at

work or when searching for work: sexual harassment,

abuse and rape. They are, therefore, subject to dual

employment discrimination due to their status as

women and refugees or migrants.

Pressure is evident in the labour market due to

informal, low productivity and precarious jobs.

There is an oversupply of labour for this type of

work, which results, on the one hand, in an increase

in job insecurity, which affects both nationals and

refugees and migrants and, on the other, an increase

in xenophobia and discrimination.

3.5 Impact on employment and

work due to the measures

adopted to stop the spread

of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a veritable health,

socioeconomic and care crisis. The quarantines

and other physical distancing measures adopted to

prevent the spread of the virus, although necessary,

generated an economic recession at the global

level that resulted in a decrease or paralysis of

productive activities, especially in sectors such as

hotels, construction, restaurants, travel and tourism;

a strong increase in unemployment and a reduction

in working hours and income (UN, 2020). The

International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that real

GDP will suffer a drop of 3% in the world in 2020 and

a drop of 5.2% in LAC (IMF, 2020). The UNDP (2020a)

anticipates that the Human Development Index (HDI)

could reverse for the rst time in three decades.

30

Migration from Venezuela: opportunities for Latin America and the Caribbean

Recent ILO estimates show a decrease in the number

of working hours of around 10.7% compared to the

last quarter of 2019, which is equivalent to some 305

million full-time jobs in the world (based on a 48-hour

workweek) and a reduction of 13% in the Americas

(ILO, 2020a). These same estimates show that many

young people under 30 years of age, who make up

around 70% of international migratory flows at the

international level (ILO, 2017b), were affected by the

closure of work centres and borders. The productive

sectors that are most affected are precisely those

with the greatest presence of young workers (ILO,

2020a).

In the world, almost 1.6 billion workers in the informal

economy were affected by isolation measures or

by working in the most affected sectors, and their

income was reduced by 60% during the rst month of

the crisis (ILO, 2020). According to the Inter-American

Development Bank (2020), the level of informality

could reach 62% in Latin America and the Caribbean,

a percentage that currently stands at 54%, according

to the ILO.

In 2020, the poverty rate could increase to 4.4% and

the extreme poverty rate to 2.6% compared to 2019,

reaching 34.7% of the Latin American population

- which is equivalent to 214.7 million people -; for

its part, extreme poverty would reach 13% - which

is equivalent to 83.4 million people (ECLAC, 2020d,

cited by ECLAC and ILO, 2020).

People who work in the informal economy and who

are therefore not covered by the countries’ social

protection systems are the ones who are most

affected by the economic and labour crisis. Refugees

and migrants, who also suffer the consequences

of xenophobia and discrimination, constitute a

particularly vulnerable population because most

of them work in activities related to commerce and

services, including itinerant sales, domestic work,

11 “Interagency Group on Mixed Migration Flows,” Colombia, which is part of the Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from

Venezuela, R4V.

caring for children and the elderly, construction and

recycling, all informally (UNDP, 2020b). As expected,

these activities will be among the most affected when

the restrictive measures adopted due to the health

crisis are totally or partially lifted. The economic

reactivation process will also depend on the

conditions in which the companies nd themselves

in order to operate again. Many had to close, lay

off staff or slow down their production, so they did

not receive or perhaps do not receive support from

governments (tax benets, extensions to pay debts,

subsidies to keep jobs, reduction of social costs, etc.)

and will have serious difculties in resuming their

activities.

Since there is not yet a vaccine, the population will

have to live with the SARS-COV-2 virus and that will

imply an adaptation of the operating rules of many of

the services in which the migrant population is or was

employed, and this will be reflected in the quantity

and quality of jobs. Health and safety regulations

at work are especially relevant in this case, and also

require adaptation to prevent the spread of the virus.

A rapid needs assessment in the context of COVID-19,

carried out in Colombia (May 2020) by GIFMM

11

,

indicates that, since preventive measures were

implemented, 20% of households report receiving