Working Group Report on Smartphone Access

Strategies Towards Universal

Smartphone Access

September 2022

Working Group Report on

Smartphone Access

Strategies Towards

Universal Smartphone Access

September 2022

iv

Acknowledgements

This report and its recommendations are a

collective endeavour drawing on contributions

and insights from the participants of the

ITU/UNESCO Broadband Commission for

Sustainable Development’s Working Group on

Smartphone Access.

The Working Group on Smartphone Access

was co-chaired by Nick Read, CEO of Vodafone

Group, Houlin Zhao, Secretary General of the

International Telecommunication Union and

Rabab Fatima, UN High Representative for

the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked

Developing Countries and Small Island

Developing States (UN-OHRLLS).

The Working Group Co-Chairs greatly and

sincerely appreciate the efforts of our Working

Group members and external experts for their

invaluable contributions, kind review, and

useful comments and feedback. The Working

Group members and experts are listed below.

This report has been informed by research

from GSMA, ITU and 19 structured expert

interviews, as well as insights from International

Trade Centre (ITC) convened focus group of

entrepreneurs (listed below) and extensive

desk research. We gratefully acknowledge all

for sharing their time and expertise to develop

the report and we extend our sincere gratitude

to H.E. Emma Inamutila Theofelus, Deputy

Minister of Information and Communication

Technology, Republic of Namibia, for sharing

her views and perspective on the topic.

We would like to acknowledge with much

appreciation the crucial role of Professor

Christopher Yoo, John H. Chestnut Professor

of Law, Communication, and Computer

& Information Science at the University of

Pennsylvania, the Working Group expert

as well as lead author of the report, and his

team at University of Pennsylvania – Dr. Leon

Gwaka, Sindhura Kammardi Sachidananda,

Sophie Roling, Shahana Banerjee, and Meghan

Moran – for conducting extensive research and

drafting this comprehensive report.

In addition, we would like to thank the following

for executing the work of the Working Group

and providing invaluable subject matter

knowledge and guidance throughout the

process: Doreen Bogdan-Martin, Alex Wong,

Nancy Sundberg, Anna Polomska, Sameer

Sharma, Karen Woo, Julia Gorlovetskaya and

Leah Mann from ITU. Heidi Schroderus-Fox,

Miniva Chibuye and Conor O’Loughlin from

UN-OHRLLS. Davide Tacchino and Kefilwe

Madingoane from Vodacom. Joakim Reiter,

Bobbie Mellor, Joe Griffin and Maleeha Khan

from Vodafone Group.

Working Group Members: Commissioners

and Focal Points

• America Móvil: Commissioner Dr. Carlos

Jarque

• Benin: Commissioner H.E. Aurélie Adam-

Soule Zoumarou and Bleck Yoro

• FAO: Commissioner Dr. Qu Dongyu,

Maximo Torero Cullen and Henry

Burgsteden

• Ghana: Commissioner H.E. Ursula Owusu-

Ekufu, Afua Mensah and Kwame Baah-

Acheamfuor

• GSMA: Commissioner Mr. Mats Granryd ,

Belinda Exelby and Luca Elmosi

• ITC: Commissioner Ms. Pamela Coke-

Hamilton, James Howe, Riefqah Jappie and

John Ndabarasa

• Intelsat: Former Commissioner Mr. Stephen

Spengler and Jose Toscano

• International Science Technology and

Innovation Centre for South-South

Cooperation: Commissioner Dato’ Lee Yee

Cheong

• Millicom: Commissioner Mr. Mauricio

Ramos, Aidan McCartan, Horacio Romanelli

and Karim Lesina

• Smart Africa: Commissioner Mr. Lacina

Koné, Thelma Efua Quaye, Osman Issah,

Calvain Nangue and Wilgon Tsib

• UNESCO: Co-Vice Chair of the

Commission, Ms. Audrey Azoulay and

Borhene Chakroun

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

v

• ZTE: Commissioner Mr. Ziyang Xu, Lei Xue

and Tian Dao

External Experts

• Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI):

Sonia Jorge and Teddy Woodhouse

• ARM: Neil Fletcher

• AST: Clemens Wolbers and Chris Ivory

• Google: Mariam Abdullahi, Vinod Nenwani

and Aleksandra Stremidlo

• HMD/Nokia: Alain Lejeune, Won Chang,

Florian Seiche and Justin Maier

• Intel: John M Roman and Turhan Muluk

• Mara Phone: Ashish J. Thakkar and Eddy

Sebera K.

• PayJoy: Deepak Murthy and Dominique

Friedl

• Softbank: Jingyi Huang, Osamu Kamimura

and Masumi Oyama

• TCT: Aaron Zhang, Ernst Wittmann and

Guoqing Yao

• Transsion: Steven Huang and Yoyo Zhang

• Trustonic: Dion Price and Craige Fleischer

• World Bank Digital Development Global

Practice: Doyle Gallegos

ITC-convened Focus Group

• Aspira (Kenya): Irshad Muttur

• FollowMeTalk (Kenya): Edwin Okoye

• Intelligra (Nigeria): Tayo Ogundipe

• Kei Phone (Uganda): Maria Nampijja

• Lipalater (Uganda): Ephraim Okalebo

• Nuovo Pay (Nigeria): Nitesh Bhalothia

• PayJoy (Nigeria): Dominique Friedl

• Superfluid (Ghana): Winifred Kotin

Disclaimer

This research report, titled Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access is based on data and

material accessible as of 31 Aug 2022 and may not reflect circumstances thereafter.

This report has been prepared, with the support of experts under the supervision of Professor

Christopher Yoo, John H. Chestnut Professor of Law, Communication, and Computer & Information

Science at the University of Pennsylvania, andthe members of the Broadband Commission Working

Group on Smartphone Access co-chaired by Nick Read, CEO Vodafone Group; Houlin Zhao,

Secretary General of the International Telecommunication Union and Rabab Fatima, UN High

Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small

Island Developing States.

The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Broadband Commission members or their organizations. This Working Group report does not

commit the Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development.

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

vi

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Acknowledgements ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv

Vodafone Group foreword

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� viii

ITU foreword

���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ix

UN-OHRLLS foreword

�������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������x

Executive summary

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������xi

Section 1: Introduction: The opportunity

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1

1.1 The benefits of Internet connectivity ................................................................................................1

1.2 Shifting focus from the “coverage gap” to the “adoption gap” ....................................................2

1.3 The “consumption gap” as the next frontier and the benefits of upgrading to

smartphones and broadband ............................................................................................................3

1.4 Mobile Internet access for sector-specific use cases ......................................................................5

Section 2: Smartphone access as a barrier to adoption

������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10

2.1 Supply-side barriers ..........................................................................................................................12

2.1.1 Supply-side barrier – handset affordability .......................................................................12

2.1.2 Supply-side barrier – last-mile supply chain issues..........................................................14

2.1.3 Supply-side barrier – foreign currency availability and exchange rate volatility .........14

2.2 Demand-side barriers .......................................................................................................................14

2.2.1 Demand-side barrier – lack of consumer understanding and information .................14

2.2.2 Demand-side barrier – lack of sufficient incentives .........................................................15

2.2.3 Demand-side barrier – digital illiteracy .............................................................................15

2.2.4 Demand-side barrier – social and cultural norms ............................................................15

2.2.5 Demand-side barrier – security and harassment .............................................................16

Section 3: Case studies and evaluation

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 20

3.1 Methodology ......................................................................................................................................20

3.2 Higher priority interventions ............................................................................................................20

3.2.1 Higher priority intervention – device financing ................................................................20

3.2.2 Higher priority intervention – taxes and import duties ...................................................26

3.2.3 Higher priority intervention - improved distribution channels ......................................31

3.3 Interventions that merit further exploration ...................................................................................34

3.3.1 Intervention for further exploration - device subsidies ...................................................34

3.3.2 Interventions for further exploration – reuse of preowned smartphones ....................39

3.4 Lower priority interventions .............................................................................................................43

3.4.1 Lower priority intervention – local manufacturing ...........................................................43

3.4.2 Lower priority intervention – smart feature phones ........................................................47

Table of contents

vii

Section 4: Translating our findings into action: A five-point plan to increase smartphone

ownership ............................................................................................................................................... 53

Conclusion..................................................................................................................................................... 56

List of figures and tables

Figures

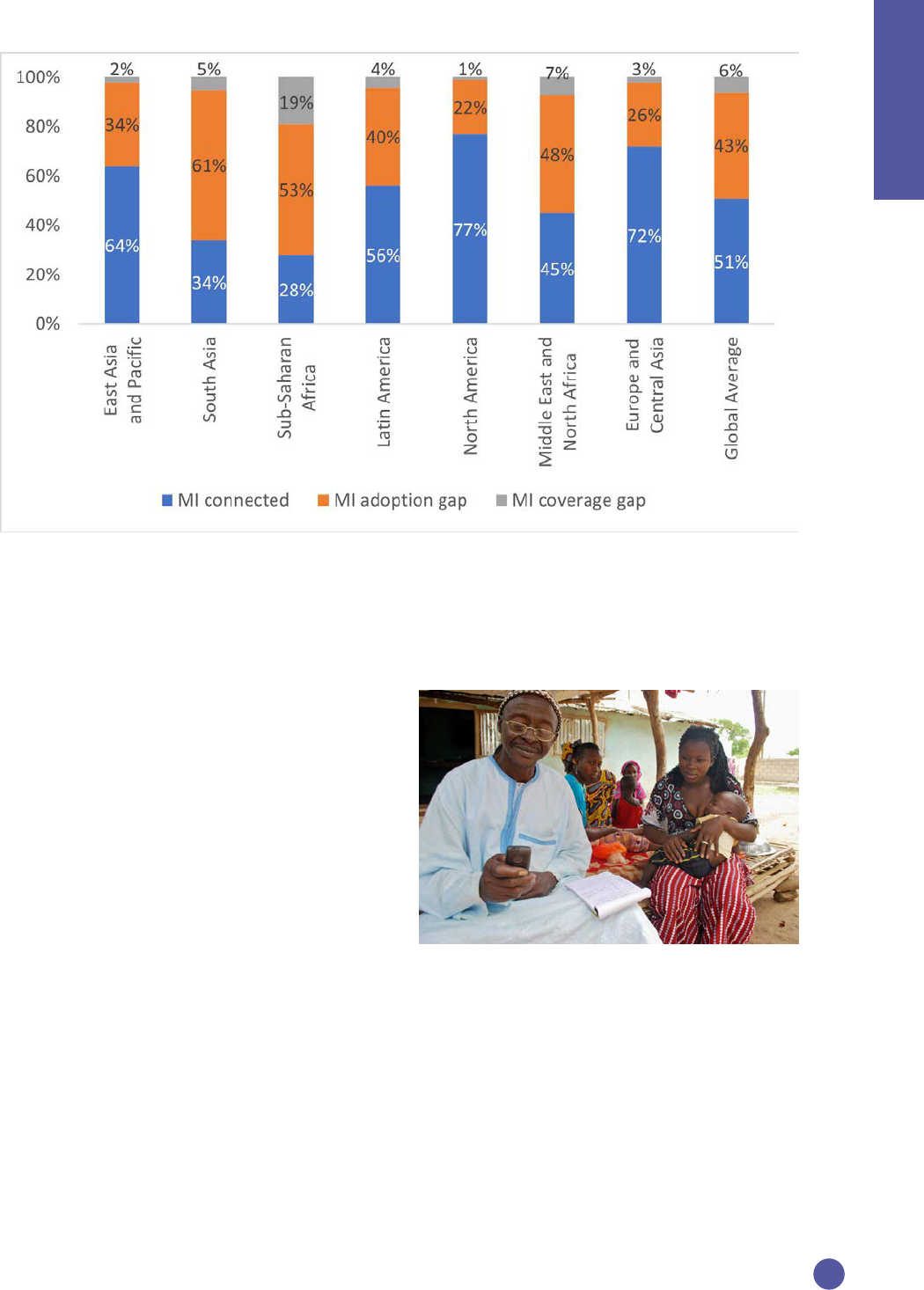

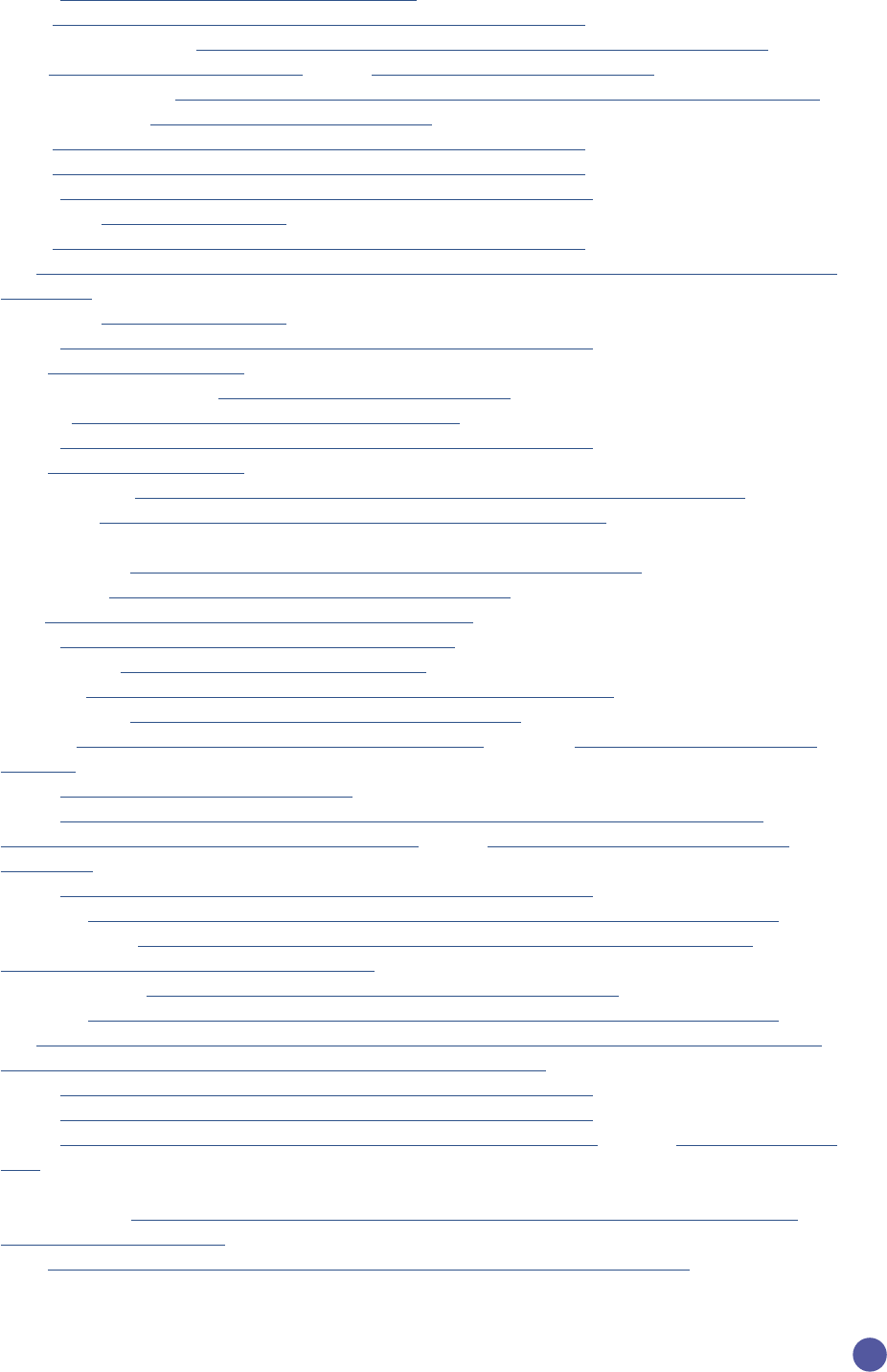

Figure 1: Mobile Internet (MI) connectedness, adoption gap, and coverage gap by region, 2020

.........................................................................................................................................................3

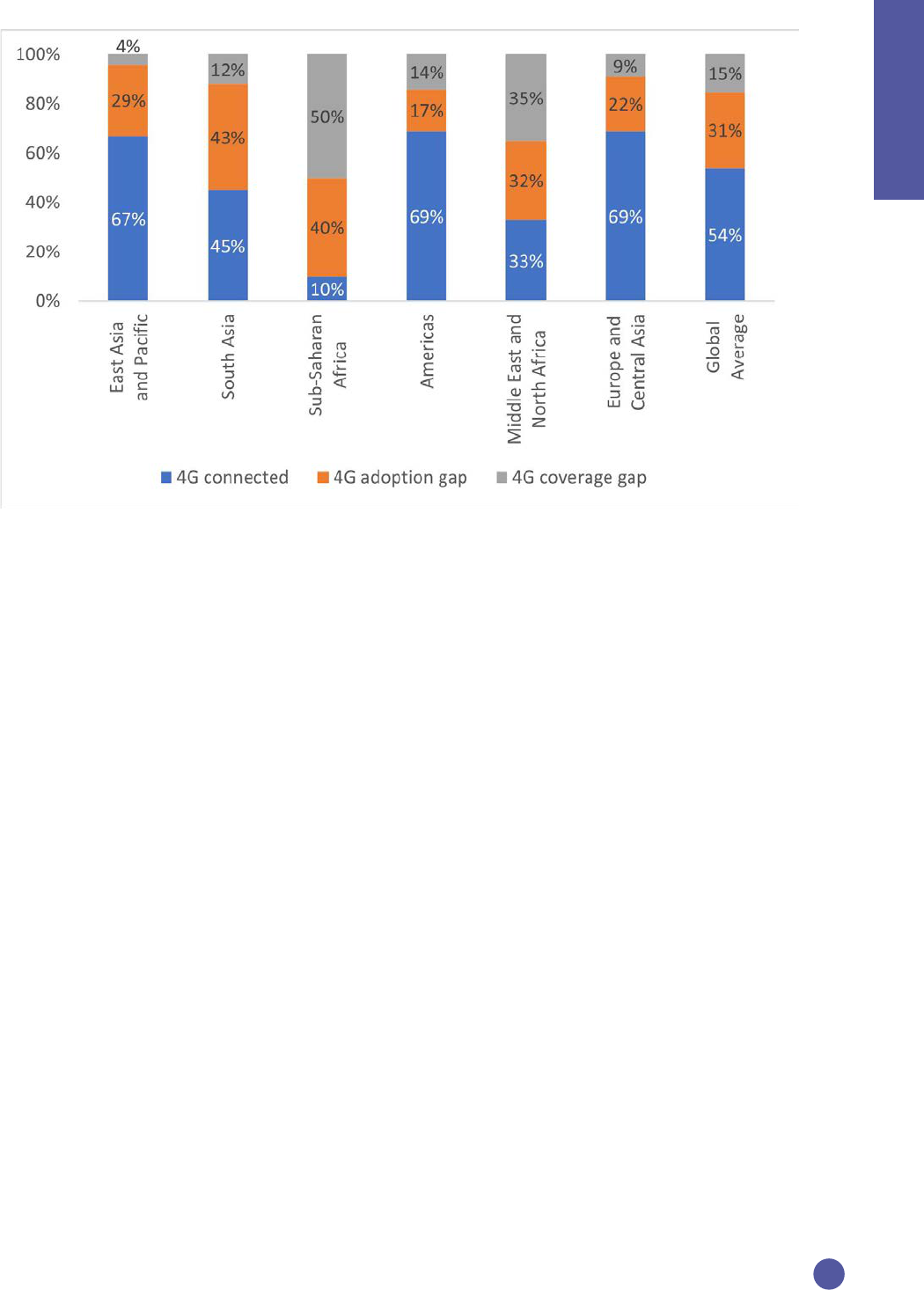

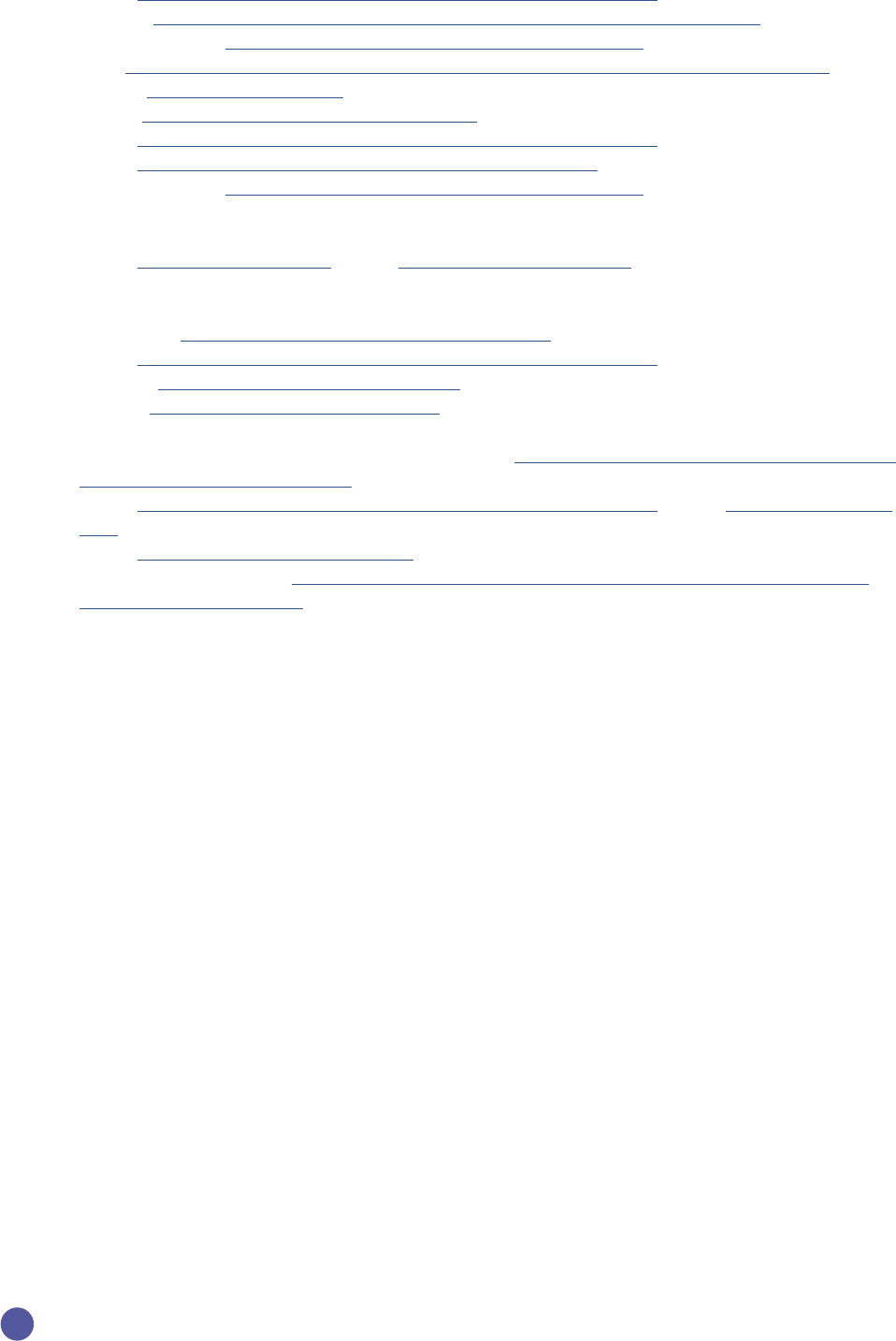

Figure 2: 4G connectedness, adoption gap, and coverage gap by region, 2019....................................5

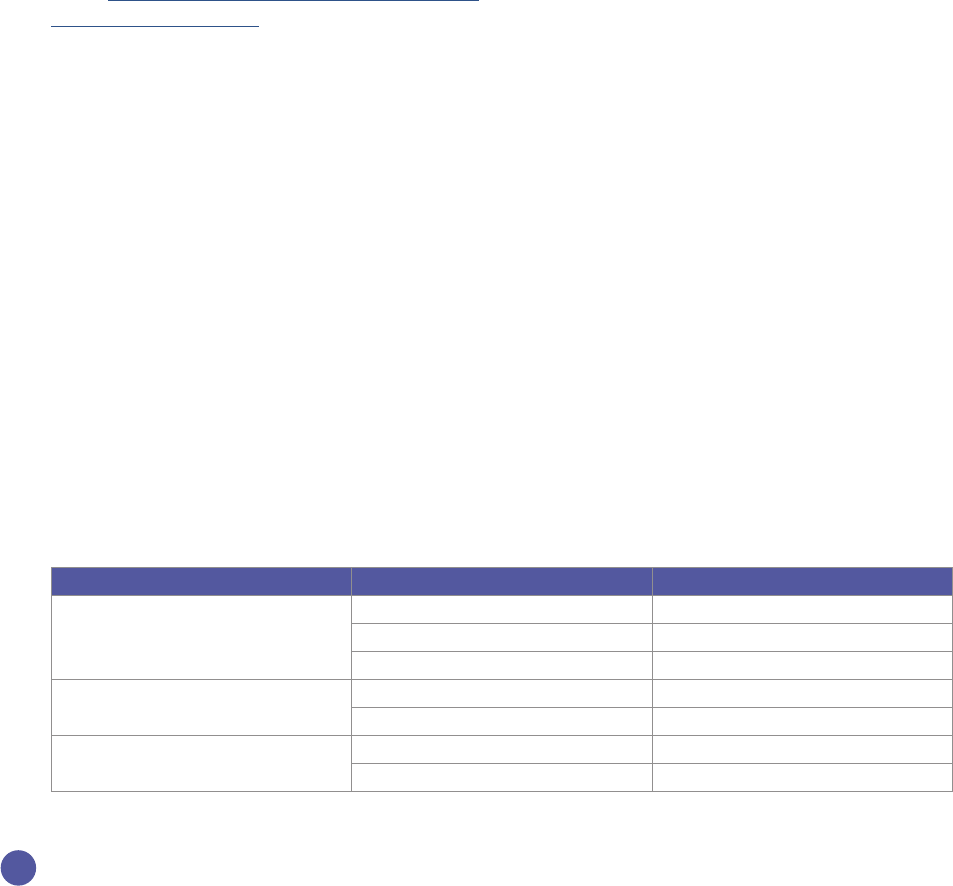

Figure 3: Main reason for not using the mobile Internet, 2019-20 ...........................................................10

Figure 4: Main reason for not having a smartphone, 2017-18 ...................................................................11

Tables

Table 1: Classification of case study interventions .......................................................................................20

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

viii

Vodafone Group foreword

Over the last ten years, our daily lives, societies and economies have been transformed by

highspeed connectivity and smartphones. We can now keep in touch with loved ones wherever they

are. We can access key health, education and government services remotely. Entrepreneurs and

small businesses can become connected and flourish. And we can entertain ourselves 24/7. Digital

connectivity is now a necessity, no longer a luxury.

Now, as much of the world stands on the edge of a 5G revolution with the potential to address

some of our biggest challenges, there are still 2.7 billion people who remain on the other side of the

digital divide, unconnected. Most of these people live in Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs),

and most are covered by a mobile broadband network.

One of the biggest barriers to access is affordable smartphones. In many LMICs they can cost over

70% of the average monthly income. However, we lacked a collaborative action plan to overcome

this barrier to connectivity. That is why in 2021 we launched the Broadband Commission’s Working

Group on Smartphone Access. This is the first ever cross-industry and government group on

affordable access to smartphones, and a continuation of Vodafone’s commitment to closing the

digital divide through our Africa.connected programme.

Over recent months, the group has studied the biggest barriers to smartphone access, and tested

initiatives designed to improve access, with the aim of producing clear recommendations to policy

makers, industry and international organisations. This report is the culmination of those efforts.

We know that if we solve the problem of global smartphone access, the benefits will be enormous.

According to the World Economic Forum, a 10% increase in access to mobile broadband would

lead to an average 1.5% increase in GDP. In Africa, the increase would be 2.5%. For the individual,

the impact is also lifechanging. Studies show that mobile Internet adoption is linked to a 3% rise in

socioeconomic wellbeing. We also know that efforts to close the digital divide must not come at the

cost of the planet, and we have explored interventions that may concurrently address growing levels

of e-waste.

This report recommends a five point action plan to increase smartphone ownership for all. It's

important that we now agree on continued cooperation to translate this action plan into positive

outcomes.

I would like to thank every member of the Working Group for the energy, expertise and insight they

contributed to this report. I look forward to working with governments, international organisations,

and other technology companies to make the recommendations of this report a reality.

Vodafone’s purpose is to connect for a better future by using technology to improve lives, digitalise

critical sectors, and enable inclusive and sustainable digital societies. To achieve this, we cannot

- and must not - leave anyone behind. By acting on the recommendations of the report, we can

ensure that is the case.

Nick Read

CEO Vodafone Group

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

ix

ITU foreword

It is with great pleasure that the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) presents this

Broadband Commission Working Group Report as a contribution towards promoting universal and

meaningful connectivity against the backdrop of a pandemic-impacted world with growing digital

inequalities.

Since it was founded in 1865, the ITU has contributed to connecting people globally with our role in

managing radio-frequency spectrum and satellite orbit resources, developing technical standards

to ensure interoperability and interconnection of networks and technologies, as well as promoting

connectivity and access to information and communication technologies (ICTs) to underserved and

unserved communities worldwide.

There have been tremendous strides in terms of connectivity, however, as at 2022, ITU estimates that

there are still 2.7 billion people worldwide who do not use the Internet. This is despite the fact that

at least 95 per cent of the world’s population live within the range of mobile broadband network.

According to the ITU Global Connectivity Report 2022, affordability and connectivity go hand in

hand. In countries where broadband is affordable, this leads to a high number of Internet users;

conversely, in countries where broadband is not affordable, there exists a high percentage of users

who are unconnected. Further, the lower the share of Internet users in a country, the less affordable

the devices are. In addition, the least mature ICT regulatory environment also goes hand in hand

with the least affordable prices in countries.

In recognizing that affordability is a key element of achieving universal connectivity, the Broadband

Commission for Sustainable Development has set the target to reduce the price of entry-level

fixed or mobile broadband services in low- and middle-income countries to less than 2 per cent of

monthly Gross National Income (GNI) per capita by 2025.

In this regard, the Broadband Commission Working Group on Smartphone Access was established

in November 2021 to address the device gap in order to enhance affordability and digital inclusion.

Co-chaired by Vodafone, ITU, and UN-OHRLLS, this group brings together members from the

Broadband Commission and external experts to examine the barriers to smartphone access and to

explore initiatives to overcome these barriers.

Thanks to the collaborative efforts of all members of the Working Group and their valuable input,

commitment and contributions, this report moves the conversation forward by providing detailed

case studies on initiatives implemented globally to address the challenges in providing affordable

broadband and smartphone access. This report is just the first step. For the next phase, I would like

to invite you to join us to implement the recommended initiatives and the five-point action plan to

reduce the device gap for the underserved communities globally, as we move towards building a

more inclusive, equitable and sustainable world.

Achieving universal and meaningful connectivity and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

requires a multistakeholder approach, and national, regional, and global collaboration on an

unprecedented scale. We invite you all to join the Broadband Commission to implement the

recommendations to address affordability, reduce the smartphone device gap and enable digital

inclusion. Our goal is to leave no one behind.

Houlin Zhao

Secretary General of the International Telecommunication Union

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

x

UN-OHRLLS foreword

For many of us – the lucky ones – the mobile phone in our hand is a link to friends and colleagues,

a first line of defence in an emergency, and a tool of research. And yet, billions of people remain

without this most fundamental form of connection. This denies whole communities economic,

educational, and social opportunities, and it holds back the earning power of less developed

nations.

The situation is most acute in the world’s most vulnerable countries – the Least Developed Countries,

Landlocked Developing Countries, and Small Island Developing States – where most of the 2.7

billion people without Internet access live. And within these countries and communities, it is often

the people already at the margins, especially women, who struggle to get online.

Indeed, this report shows that women in low- and middle-income countries are 18% less likely than

men to own a smartphone. This exclusion is worse in the least developed countries, especially in the

most rural areas, and it reinforces and exacerbates their marginalisation.

Smartphone exclusion also acts as a significant brake on growth: a strong correlation exists between

access to mobile Internet services and GDP, with studies showing that as little as a 10% access

increase in 3G services or higher can deliver as much as a 2.46% growth in GDP in low- and middle-

income countries in Africa, and 2.44% in Asia-Pacific.

Infrastructure challenges remain, but this is a crisis of adoption, not connectivity. Mobile coverage is

widely available, but Internet uptake and usage remain low. This report proposes a plan to bridge

that digital divide with clear recommendations based on evidence and lived experience.

In the short term, governments should reduce tax and duties on devices to reflect their growing

centrality to developing economies and telecom operators should introduce more flexible

financing and improved distribution focusing on the most marginalised, especially women and rural

communities.

And in the long term, tackling value chain issues, and greatly improving device recycling, can close

the Internet adoption gap. Like a new train with no passengers, there is little benefit from increasing

Internet coverage without adoption and access.

This is the first time a report of this kind has presented new strategies for universal smartphone

access, and I want to thank my co-chairs from ITU and Vodafone for their leadership and vision,

as well as the rest of the working group for their guidance and expertise. And to the Broadband

Commission, under whose leadership this work has been commissioned, I offer my unwavering

support and that of my office to support the delivery of the solutions proposed herein.

For individuals, institutions and nations alike, the benefits are clear; universal smartphone access can

change lives, bridge divides, and boost economies. We must share these benefits and opportunities

with all.

Rabab Fatima

UN High Representative for the Least Developed Countries,

Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

xi

Executive summary

An estimated 2.7 billion people globally remain offline today. Most of these people are in low- and

middle-income countries (LMICs), and most of them live within good Internet coverage. However,

the cost of a smartphone to access the Internet can exceed 70% of the average income in LMICs,

presenting a significant barrier to digital inclusion.

The adoption gap for mobile Internet – which arises when people do not use the Internet even when

there is mobile network coverage available – is now over seven times larger than the coverage gap

globally.

Furthermore, most people in LMICs who do access the Internet are still using 2G and 3G, which

is preventing them from realizing the full social and economic benefits of high-speed Internet

connectivity.

This study represents the first multi-stakeholder dialogue and analysis on the topic of smartphone

access, under the ITU/UNESCO Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development.

This report examines the barriers to smartphone ownership and usage, and provides

recommendations based on empirical evidence to overcome those barriers, with a special focus

on LMICs. The report categorises the assessed interventions into; “High Priority” interventions,

interventions that “Warrant Further Investigation”, and “Low Priority” interventions. These findings

have been informed by research from GSMA, ITU and 19 structured expert interviews, as well as

insights from an ITC-convened focus group of entrepreneurs, and extensive desk research.

The report’s actionable recommendations are designed to guide stakeholders when determining

how to address smartphone access challenges, and provide a clear roadmap forward.

Key findings

The research found three high priority interventions that are proven to increase smartphone

ownership:

1. Smartphone financing schemes

2. Reduction of taxes and import duties on smartphones

3. Improvement of smartphone distribution channels

We also found two interventions that warrant further investigation:

1. Device subsidies

2. Increasing use of refurbished/preowned devices

Two interventions studied were classified as low priority, meaning that they lacked evidence of

increasing smartphone ownership at scale, but may achieve results at a smaller scale in some

countries:

1. Local manufacturing

2. Supply of smart feature phones

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

xii

Translating our findings into action: a five-point plan to increase smartphone ownership

This report has been created as a starting point for policymakers, governments, and businesses

to take action on increasing smartphone access. As such, the report provides a five-point action

plan to translate the findings into action, outlined below. Most of the actions require cross-party

collaboration and, as such, the report recommends the establishment of taskforces to drive concrete

commitments, conduct further research, and implement pilots.

Action 1: Initiate win-win partnerships with players across the digital value

chain

Action 2: Improve regulation on smartphone recycling and develop quality

standards for preowned smartphones

Action 3: Develop strategies for recycling of mid- and lower-tier devices

Action 4: Explore the use of Universal Service Funds and other government

subsidies for smartphones

Action 5: Further explore the overall economic benefits of reducing tax and

import duties on smartphones

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

1

1

Introduction:

The opportunity

1

Section 1: Introduction: The opportunity

1�1 The benefits of Internet

connectivity

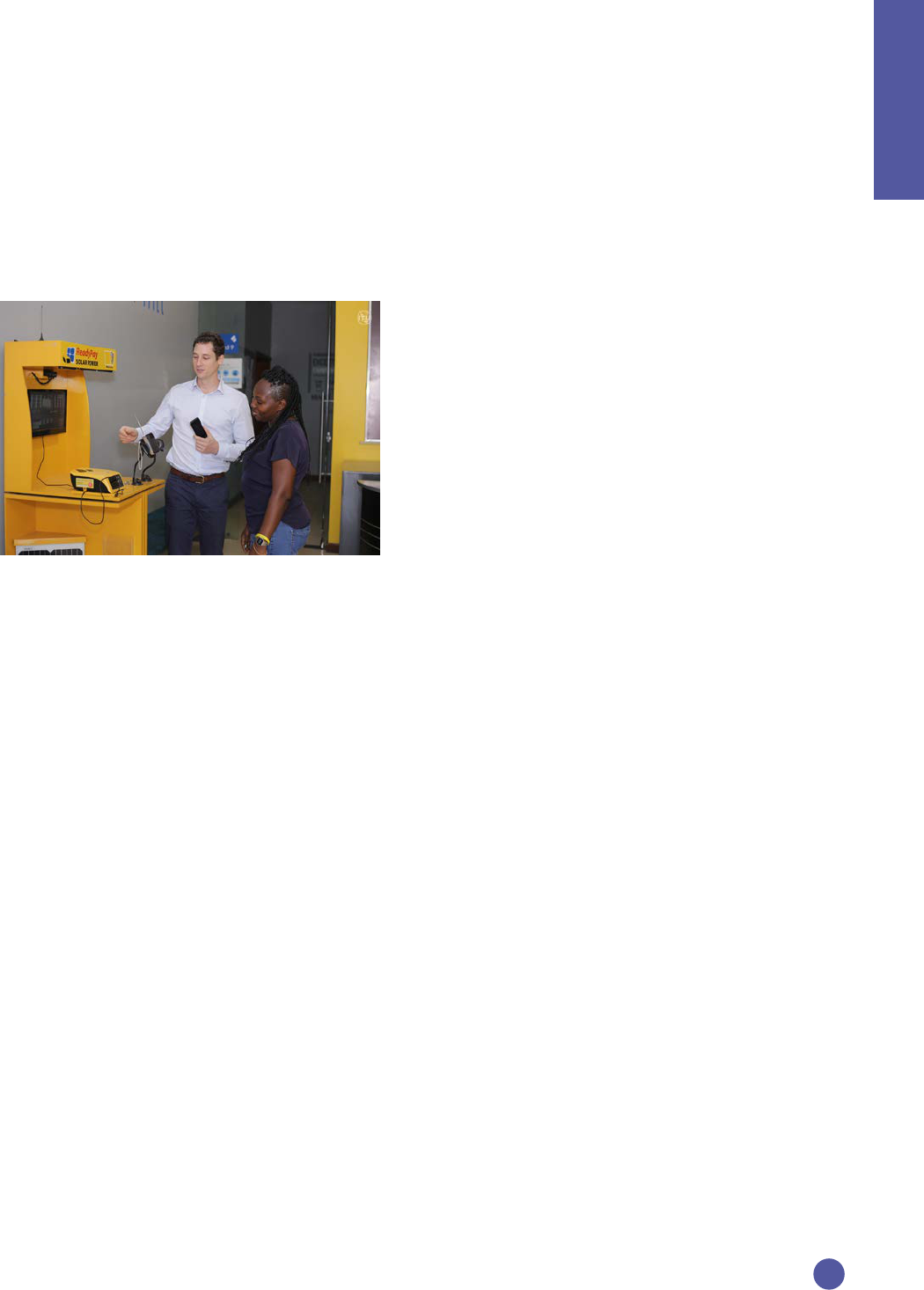

Photo credit: ©Asian Development Bank

The policy debate over the global digital

divide and digital equity is undergoing a

fundamental transformation. A growing body

of empirical research has demonstrated the

economic and social benefits of connecting

people.

1

Any remaining doubts were effectively

laid to rest by the COVID-19 pandemic,

which eloquently demonstrated the key role

that Internet access plays in critical areas

such as agriculture, education, health care,

remote working, economic development,

public services delivery, financial services,

and disaster recovery. A recent International

Telecommunication Union (ITU) study estimates

that the number of Internet users surged by

800 million people in 2020.

2

That study also

estimates that 97% of the world population

now has access to a mobile cellular data

network, and that 95% has access to at least

a 3G signal, and the quality of broadband

has also improved with 4G network coverage

doubling between 2015 and 2021 to reach

88% of the world’s population. Mobile phones

continue to be the primary way, and in many

cases, the only way, most people access the

Internet, particularly in low- and middle-income

countries (LMICs).

3

Wi-Fi is also a standard

feature of smartphones that people use to

access the Internet in homes, public hotspots,

and community centres.

Despite these gains, in 2022, an estimated

2.7 billion people still cannot or do not access

the Internet.

4

Furthermore, most of those still

offline live in fragile and conflict-affected areas,

least developed countries (LDCs), landlocked

developing countries (LLDCs) and small

island developing states (SIDS). By way of

comparison, 92% of residents in high-income

country populations are Internet users, while

adoption rates in SIDS (66%), LLDCs (36%),

and LDCs (36%) continue to lag far behind.

5

Research has also shown that overcoming the

barriers to mobile Internet adoption would

yield substantial benefits. Studies conducted

at a national or similarly large-scale level

consistently found that Internet adoption has a

positive impact on national GDP. For example,

the ITU estimates that a 10% increase in fixed

broadband adoption yields a 1.4% increase in

GDP in Europe, 1.9% in the Americas, and 2.5%

in Africa.

6

Other studies have corroborated

these findings:

•

A Broadband Commission study of

Rwanda, Senegal, and Vanuatu from

2010-16 estimates that the information and

communications sector contributed to a

0.3% to 0.5% increase in GDP.

7

• A study of 220 towns in 10 sub-Saharan

African countries employing a new

methodology that uses satellite images of

night-time lights as a proxy for changes

in economic activities estimates that basic

Internet coverage leads to a 2% increase in

economic growth rates.

8

Studies of benefits to individual wellbeing are

beginning to emerge as well.

9

, For example,

surveys of individual users conducted in

Bangladesh and Ghana in 2020 found that

mobile Internet adoption is associated with

a 3% increase in individual socioeconomic

wellbeing, with the effect being larger among

women (4% to 6%) and those with at least

a primary education (5%).

10

Wellbeing is

enhanced by broader access to financial

services, e-commerce, and government

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 1

2

services.

11

Other studies have found that

Internet access increases women’s participation

in society as well as their social and economic

resilience.

12

Due to COVID-19 and its consequent

lockdowns and social distancing measures,

people relied on their mobile networks to stay

connected with each other and the rest of

the world. Despite the pandemic’s impact on

the economy and consumer incomes, mobile

adoption continued to increase in 2020,

justifying the mobile industry’s contribution

to the UN Sustainable Development Goals

(SDGs). Some contributions to SDGs included

increased use of mobile financial services,

access to government services, and online

learning.

13

Mobile Internet connectivity also creates

benefits during natural disasters both in terms

of sending early-warning alerts to people and

allowing them to share information about

the disaster with authorities.

14

Furthermore,

mobile devices improve coordination and

rescue efforts by enabling rescue teams to

communicate and access key information such

as visuals required for planning.

15

Access to

the Internet is particularly beneficial to women

faced with natural disasters or other threats

that force them to become refugees.

16

During

disasters, vulnerable groups, including persons

with disabilities, can use new technologies to

share their location and improve their chances

of receiving assistance. Applications such as

Facebook Disaster Maps help rescue teams

and victims to establish their location during

disasters.

17

Similar applications and other technologies

are being used to collect data essential for

reviews of disasters.

18

Given the importance

of technologies before, during, and after

disasters, equitable access and use of

technologies, especially among women,

is therefore important.

19

Next generation

technologies, including smartphones and

4G/5G, promise improved approaches and

coordination before, during, and after the

disaster.

20

For example, Google’s earthquake

detection and alert application for smartphones

can help people to prepare before disaster

strikes.

21

Governments can also derive several benefits

from increased access to smartphones among

the citizens. Research shows that smartphones

enhance opportunities for digital government

and citizen engagement. There is evidence that

increased smartphone access enables more

citizens to participate on social media platforms

that have augmented traditional channels to

interact with governments, report concerns,

and provide feedback.

22

In addition, increased

smartphone access also enables sourcing of

open public data that governments can use to

make real time decisions.

1�2 Shifting focus from the “coverage

gap” to the “adoption gap”

Until recently, investments to close the

connectivity gap have focused on rolling

out infrastructure to expand mobile Internet

coverage. These efforts have achieved a

significant degree of success.

The ITU estimates that in 2021, 95% of the

world's population was covered by at least a 3G

signal. Moreover, of the 2.7 billion who remain

offline, only 390 million were not covered by a

mobile Internet 3G signal or better, although

these shortfalls are not evenly distributed.

Specifically, more than 99% of people in

high-income countries have access to mobile

coverage, while only 86% of residents of low-

income countries do.

23

Rural coverage rates lag

behind urban rates as well with respect to basic

mobile cellular coverage (100% for urban areas

vs. 93% for rural areas, for a disparity of 7%),

3G coverage (100% for urban areas vs. 88%

for rural areas, for a disparity of 12%), and 4G

coverage (97% for urban areas vs. 75% for rural

areas, for a disparity of 22%). The urban-rural

disparity is particularly severe in LLDCs (69%),

LDCs (54%), and SIDS (46%).

24

Despite the success in extending mobile

broadband coverage to an ever-increasing

proportion of the world’s population, a large

number of people have access to a network

but remain offline. The significant number

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

3

of people who have the opportunity to

adopt the Internet but choose not to do so

underscores the need to refocus efforts to close

the digital divide beyond merely expanding

coverage. Policymakers need a more complete

understanding of the barriers to mobile

Internet adoption and how to overcome

them. Studies have increasingly shown that

in addition to “coverage gaps,” the digital

divide is also the product of an “adoption gap,”

which arises when individuals do not use the

Internet even when mobile network coverage

exists.

25

Figure1 shows that the worldwide

adoption gap of 43% is much larger than the

6% coverage gap, with the adoption gaps in

South Asia (61% vs. 5% coverage gap), sub-

Saharan Africa (53% vs. 19% coverage gap),

and the Middle East and North Africa (48% vs.

7% coverage gap) all exceeding the global

average. The size of these adoption gaps

makes clear that significant barriers to adoption

exist aside from coverage.

1�3 The “consumption gap” as the

next frontier and the benefits of

upgrading to smartphones and

broadband

Photo credit: ©OCHA / IRIN

Studies have found that accessing the Internet

through feature phones connected to 2G

networks can enhance economic and social

welfare.

27

However, there are suggestions

that users can gain further benefits by moving

beyond 2G and 3G and connecting to high-

speed broadband services such as 4G and

eventually 5G. For example, a GSMA working

paper studying a panel of 160 countries found

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 1

Figure 1: Mobile Internet (MI) connectedness, adoption gap, and coverage gap by region,

2020

Source: GSMA

26

4

that upgrading from 2G to 3G increases the

GDP impact of mobile connectivity by 15% and

that upgrading from 2G to 4G increases the

impact by 25%.

28

Analyses that attempted to

identify how broadband connectivity conveys

benefits further underscore the importance of

4G adoption. A World Bank study identified

six foundational online activities—news,

government, health, education, shopping, and

social media—and that realizing the benefits

of these foundational activities requires a

minimum of 6GB per month.

29

A4AI has

emphasized that realizing the benefits of these

more advanced services requires “meaningful

connectivity” that allows individuals to use the

Internet every day using an appropriate device

with enough data and a fast connection.

30

Consistent with this concern, industry observers

have cautioned that the fact that most mobile

Internet users are still using 2G and 3G in most

LMICs is preventing them from realizing the

full benefits of Internet connectivity.

31

Using

education as an example, 2G and 3G support

file sharing only in limited formats, while 4G

and 5G can deliver seamless online interactions

such as video tutorials and interactive learning

exercises.

32

Available data suggest that adoption of mobile

broadband would enable users to access these

services. For example, upgrading users from

2G to 3G increases their data capacity by 9.4

times and data performance by 112 times.

Upgrading users from 3G to 4G increases data

capacity by 4.2 times and data performance by

4.6 times. 5G is expected to deliver higher peak

data speeds, lower latencies, and higher data

capacity. By 2027, 5G subscriptions across the

globe are forecast to reach 4.4 billion, nearly

half of all mobile subscriptions.

33

Studies conducted at the country level have

consistently found that adoption of mobile

broadband services such as 3G, 4G, and 5G

would provide significant economic and social

benefits:

•

An ITU study of 145 countries between

2010-18 found that a 10% increase in

unique subscriber penetration for 3G or

higher services yielded a 1.50% increase

in GDP driven by a 1.76% increase in

middle-income countries and a 1.98%

increase in low-income countries.

34

This

effect was particularly strong in Africa

(2.46% increase), Asia Pacific middle- and

low-income countries (2.44%), European

low-income countries (2.00%), Arab states

(1.82%), and Latin American and Caribbean

states (1.73%).

•

A UN-OHRLLS and ITU study of 91 LDCs,

LLDCs, and SIDS from 2000-17 found that

a 10% increase in 3G, 4G, and WiMAX

penetration generated a 2.8% increase in

GDP.

35

• IHS Markit has predicted that by 2035,

5G will enable USD 13.2 trillion of global

economic output and will represent about

5.0% of all global real output.

36

Studies conducted at the household level

that used consumption as a proxy for income

corroborated these findings:

•

Surveys conducted in Senegal in 2011 and

2017 indicate that household consumption

is 14% higher and that the extreme poverty

rate is 10% lower in areas covered by 3G.

37

• Three rounds of household surveys

conducted in Nigeria between 2010-16

revealed that at least one year of 3G or 4G

mobile broadband coverage increased

household consumption by 6% and

reduced extreme and moderate poverty by

4.3% and 2.6% respectively.

38

• Three rounds of surveys administered in

Tanzania between 2008 to 2013 found that

3G coverage was associated with a 10%

increase in household consumption and

that one year of coverage was associated

with a 3%-8% increase in labour force

participation, wage employment, and non-

farm employment.

39

The benefits from 3G, 4G, and 5G mobile

broadband connectivity appear to have

increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, a new ITU study that extended

the previous ITU study found that including

2019 and 2020 in the analysis caused the GDP

increase associated with a 10% increase in

mobile broadband penetration to grow from

1.50% to 1.60% worldwide, driven by a 2.04%

increase in GDP in low-income countries and

a 162% increase in GDP growth in middle-

income countries.

40

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

5

Despite the benefits that come from adopting

3G and 4G mobile broadband services,

adoption rates remain low. This problem is

especially prominent in LMICs.

4G adoption similarly continues to lag,

although 4G coverage gaps remain significant

in some areas. The ITU reports a global 4G

adoption gap of 31% vs. a coverage gap of

15%. The adoption gap exceeds the global

average in South Asia (43% vs. 12% coverage

gap) and sub-Saharan Africa (40% vs. 50%

coverage gap), and Middle East and North

Africa (32% vs. 35% coverage gap).

These data suggest that simply closing the

coverage gap (by extending mobile networks

to cover unserved areas) and closing the

adoption gap (by getting people with access

to a mobile signal to subscribe) would not be

enough to ensure that people obtain the full

benefit of Internet connectivity. Policymakers

must also address what the World Bank calls

the “consumption gap,” which arises when

Internet data consumption among people

who have adopted the Internet remains low.

42

Closing the consumption gap will require

interventions beyond those necessary to close

the coverage gap and the adoption gap.

Beyond providing simple network connectivity

and a device capable of connecting to the

mobile Internet, enabling people to use the

full capabilities that the Internet has to offer

requires extending higher level connectivity

(4G and 5G) and expanding access to higher

level devices such as smartphones.

1�4 Mobile Internet access for sector-

specific use cases

In addition to individual level use of

connectivity, research shows the importance

of the mobile Internet at an institutional level.

Mobile Internet is reported to support activities

in agricultural, educational, and health-

care institutions. However, use patterns and

mechanisms are likely to vary across sectors.

43

The different use patterns result in demands

for different levels of connectivity and devices

across different institutions. For example,

schools need more devices and power than

clinics, with a typical school needing at least

one device per every two students. In contrast,

a clinic, depending on its size, could get by

with a few devices at crucial points of care for

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 1

Figure 2: 4G connectedness, adoption gap, and coverage gap by region, 2019

Source: ITU

41

6

registering patients, consulting patients, and

managing medicines.

44

The fact that this Working Group’s charter

focusses on smartphone access inevitably drew

attention away from issues surrounding access

to laptops, tablets, and other similar devices.

The relative lack of attention on other types

of devices in this report reflects that no study

can address every aspect of every issue and is

not meant to suggest that that such issues are

unimportant.

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Photo credit: ©Asian Development Bank

7

1

Hjort and Tian: The Economic Impact of Internet Connectivity in Developing Countries; Vergara-Cobos and

Malásquez: Digital Technology Adoption and the Jobs and Economic Transformation Agenda: A Survey;

ITU: The State of Broadband 2021.

2

ITU: Measuring Digital Development: Facts and Figures 2021.

3

GSMA: The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity 2021; ITU: Connect2Recover: A new methodology for

identifying connectivity gaps and strengthening resilience in the new normal.

4

ITU: Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2022 (forthcoming).

5

ITU: Measuring digital development: Facts and Figures 2022 (forthcoming).

6

ITU: How broadband, digitization and ICT regulation impact the global economy: Global econometric

modelling.

7

Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development: Working Group on Broadband for the most

vulnerable countries.

8

Min et al.: Light every night – New nighttime light data set and tools for development; Goldbeck and

Lindlacher: Digital infrastructure and local economic growth: early Internet in Sub-Saharan Africa.

9

A4AI: The costs of exclusion: South Asia regional report; GSMA: The impact of mobile on people’s

happiness and well-being.

10

Yoo et al.: Exploring the Deep Structure of Mobile Internet Use Patterns in Bangladesh and Ghana

(Unpublished Report, University of Pennsylvania).

11

ITU: Connectivity in the least developed countries: Status report 2021; GSMA: 2021 mobile industry impact

report: Sustainable development goals.

12

A4Ai: The costs of exclusion: South Asia reginal report; A4AI: The costs of exclusion: West Africa regional

report.

13

GSMA: 2021 mobile industry SDG impact report.

14

ITU: Women, ICT and emergency telecommunications: opportunities and constraints; ITU: Utilizing

telecommunications/information and communication technologies for disaster risk reduction and

management.

15

Rawat et al.: Towards efficient disaster management: 5G and device to device communication.

16

Mallalieu: Women, ICT, and emergency telecommunications: opportunities and constraints.

17

ITU: Utilizing telecommunications/information and communication technologies for disaster risk reduction

and management.

18

ITU: Utilizing telecommunications/information and communication technologies for disaster risk reduction

and management.

19

ITU: Women, ICT and emergency telecommunications: opportunities and constraints.

20

Rawat et al.: Towards efficient disaster management: 5G and device to device communication.

21

Google: Earthquake detection and early alerts, now on your Android phone.

22

Republic of Kenya: Kenya digital economy. Digital economy blueprint – powering Kenya’s transformation

23

ITU: Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2021.

24

ITU: ITU world telecommunication/ICT indicators database.

25

ITU: The State of Broadband: People-Centered Approaches for Universal Broadband.

26

GSMA: Accelerating mobile Internet adoption: Policy considerations to bridge the digital divide in low- and

middle-income countries. The data from GSMA is based on 2020, and note there is difference with ITU data

in 2021 and 2022 cited in the report.

27

Mensah, J. T: Mobile phones and local economic development: A global evidence.

28

GSMA Intelligence: Mobile technology: Two decades driving economic growth.

29

Chen and Minges: Minimum data consumption: How much is needed to support online activities, and is it

affordable?.

30

A4AI: Advancing meaningful connectivity: Towards active & participatory digital societies.

31

GSMA: Closing the coverage gap: How innovation can drive rural connectivity; Vodafone: Next-generation

mobile connectivity.

32

GSMA: The WRC series Study on socio-economic benefits of 5G Services provided in mmWave Bands.

33

Ericsson: Ericsson Mobility Report 2021.

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Endnotes

8

34

ITU: How broadband, digitization and ICT regulation impact the global economy: Global econometric

modelling.

35

ITU and UN-OHRLLS: Economic impact of broadband in LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS: An empirical study.

36

IHS Markit: The 5G economy: How 5G will contribute to the global economy.

37

Masaki et al.: Broadband Internet and household welfare in Senegal.

38

Bahia et al.: The welfare effects of mobile broadband Internet: Evidence from Nigeria.

39

Bahia et al.: Mobile broadband Internet, poverty, and labor outcomes in Tanzania.

40

ITU: How broadband, digitization and ICT regulation impact the global economy: Global econometric

modelling; ITU: The economic impact of broadband and digitization through the COVID-19 pandemic:

Econometric modelling.

41

ITU: Connecting humanity: Assessing investment needs of connecting humanity to the Internet by 2030.

42

World Bank: World Development Report 2021.

43

Economist Intelligence Unit: Bridging the digital divide to engage students in higher education.

44

Lane: Smart Business Models Are Needed to Connect Schools & Clinics.

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

1

2

Smartphone access

as a barrier to

adoption

10

Section 2: Smartphone access as a barrier to

adoption

The fact that many people do not adopt

mobile broadband even when it is available

underscores that closing the digital divide is not

simply a matter of extending network coverage.

Policymakers wishing for their people to realize

the benefits of Internet connectivity must

understand the other potential barriers to

adoption.

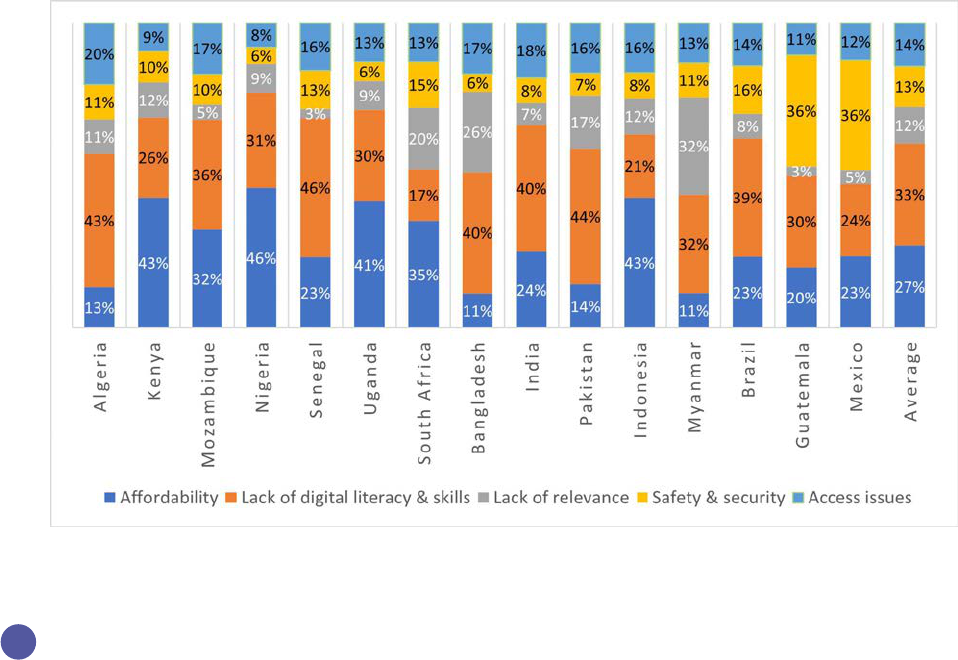

A study conducted of mobile users who do not

use mobile Internet in 15 countries in 2019-20

found that lack of access to devices was the

second-most frequently cited reason for not

using the Internet (Figure3).

This insight was confirmed by a World Bank

phone survey of 22 Latin American countries

conducted in June-July 2021, which found that

lack of access to a network signal was only the

third-most cited obstacle to Internet access

(10%), behind the high cost of data (60%) and

device cost (14%), and ahead of the lack of

digital skills (4%).

2

Other studies similarly report

that the adoption gap is the product of several

factors, including affordability of both devices

and data, lack of digital skills, relevance, and

inadequate safety and security, among others.

3

Access to a device thus emerges as one of

the critical barriers that must be overcome

for people to be able to access the Internet.

Enjoying the benefits of higher speed services

such as 4G requires access to not just any

device; it requires access to a smartphone.

Obstacles to smartphone ownership exist

worldwide but are particularly acute in lesser

developed areas of the world. A Pew Research

Centre study that compared smartphone

ownership in 19 advanced economies and

nine emerging economies found that the

percentage of adults owning any kind of mobile

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Figure 3: Main reason for not using the mobile Internet, 2019-20

Source: GSMA

1

11

phone reached 94% in advanced economies

and 83% in emerging economies.

4

However, in

terms of adults owning a smartphone, the gap

between advanced and emerging economies

widens. At least 76% of adults in advanced

economies own a smartphone compared

to only 45% in emerging economies. As an

example, at the end of June 2019, MTN had

240 million subscribers on its network in Africa

and the Middle East but only 108 million of

these were using smartphones.

5

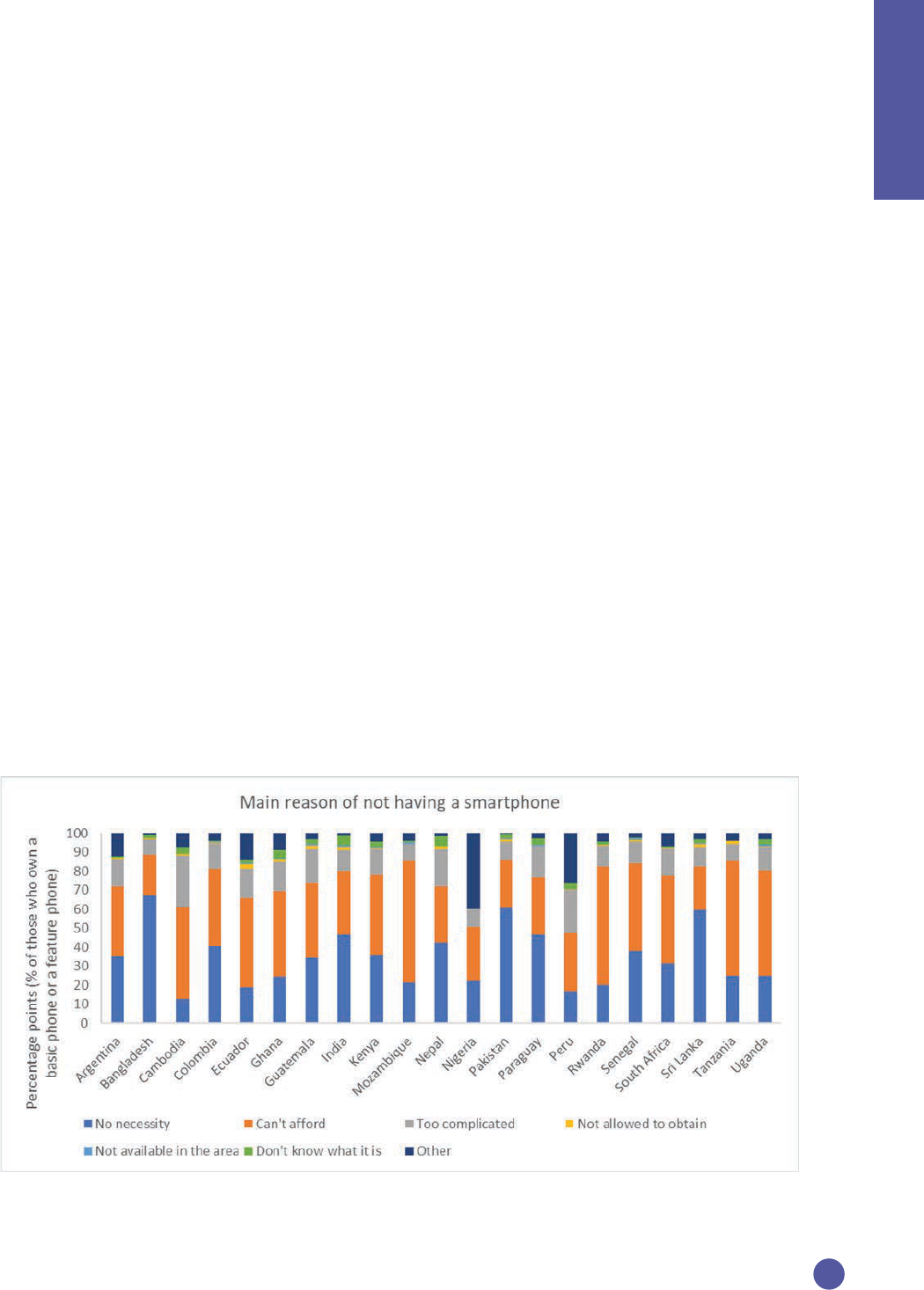

A World Bank phone survey conducted in

2017-18 among owners of a basic mobile

phone in 22 countries across Africa, Latin

America, and Asia found that the reasons for

not owning a smartphone include affordability

(39%), lack of electricity at home (18%), and lack

of mobile coverage (16%). Moreover, around

70% of phone owners have only a basic or

feature phone, particularly in African countries.

The study also finds that affordability is among

the top three reasons that device owners have

chosen not to obtain a smartphone in every

country surveyed.

6

As shown in Figure 4, many factors contribute

to the lack of access to smartphones. Efforts

to address these challenges have been

hindered by a lack of concrete information

regarding their relative importance and the

effectiveness of interventions to address them.

An extensive review of literature suggests that

a study by GSMA presents one of the more

comprehensive lists of barriers to smartphone

access.

8

This study classifies the barriers to

smartphone access and ownership into four

main categories: income and affordability,

incentives to own and use a smartphone, user

capability and design, and infrastructure.

Understanding barriers to device access is thus

a critical step in making sure that everyone can

enjoy the benefits of Internet connectivity.

In this report, we classify the barriers to

smartphone access into two main categories:

supply-side and demand-side, each with

its own subcategories.

9

Other barriers

to smartphone access, such as device

refurbishment, fall into neither the supply nor

demand-side category. These are discussed

further in the report with the help of existing

literature such as Chen.

10

We also note that

productivity applications in key sectors, such

as agriculture, education, manufacturing, and

health care, may require devices with larger

form factors, such as laptops and tablets.

11

However, several questions remain: For

example, in what context are different devices

relevant? Even when this is answered, there is

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 2

Figure 4: Main reason for not having a smartphone, 2017-18

Source: Chen

7

12

a need to establish the impact that universal

access to device has across social groups.

2�1 Supply-side barriers

Supply-side barriers are constraints that device

suppliers face when attempting to deliver

affordable devices. These mainly result from

business limitations, such as high operating

costs and legacy business models.

12

These

barriers affect the retail prices for smartphones

and distribution channels respectively.

2�1�1 Supply-side barrier – handset

affordability

Handset affordability is one of the most

important barriers to smartphone access and

ownership.

13

Despite the continued decline in

the cost of Internet-enabled handsets, retail

prices of smartphones vary widely across the

globe, driven by factors such as distribution

costs and taxes.

14

Handset affordability appears to affect women

more than men in many low- and middle-

income countries and is cited as the top barrier

preventing women from owning a mobile

phone.

15

In Pakistan, for example, men were

approximately three times more likely to own a

mobile phone than women.

16

Retail costs of handsets

A GSMA survey on barriers to mobile Internet

use reported that handset cost was the single

most important barrier to using the mobile

Internet.

17

The cost of smartphones remains

high relative to average income, especially in

LMICs. A survey of 187 countries conducted

by A4AI suggests that the retail cost of a

smartphone averages 26% of the average

monthly income across the globe. In the

U.S. and Europe, the cost fell below 5% of

the average monthly income, while in the

low-income countries, it exceeds 70%.

18

As

a result, smartphones are not affordable for

most people in most LMICs. This pushes most

individuals to buy 2G phones, which can cost

between USD 6-10, while 4G smartphones

often cost more than USD40.

An analysis of the handset cost composition

and retail price formation indicates that the

retail cost of a device is determined by a

combination of production costs, logistics

costs, intellectual property rights costs, retailers’

margins, and relevant taxes, such as import

duties and VAT. Research further suggests

that the global technology value chain has

been undergoing significant transformations

in recent years, but the onset of the COVID-19

pandemic exacerbated the already present

tension and created excess demand in

the chipset supply sector.

19

Despite new

innovations, the retail costs of mobile handsets

continue to be influenced by the costs of

hardware and operating systems.

20

Additionally,

the disruption of global and local logistics

caused smartphone prices to rise during the

early days of the pandemic

21

only to see them

fall again in response to oversupply in the face

of softening demand.

22

The spectre of further

lockdowns could cause prices to rise again.

23

High taxes and device import duties on

smartphones

Although taxes and import duties are factored

in the retail prices discussed above, they are

a policy component and warrant a separate

discussion. Evidence from studies such as

GSMA indicates that different governments,

especially in LMICs, have been imposing

sector-specific taxes and import duties on

smartphones that makes them inaccessible

to many.

24

Taxes on smartphones vary from

country to country, and justifications for

imposing import taxes on smartphones include

stimulating local industry. However, in countries

where local industry is non-existent, taxes and

duties on mobile phones are imposed to boost

government revenue.

25

In addition, some governments, especially

in Africa, are levying taxes on smartphones

in a way similar to luxury goods, resulting

in excessively high final prices for devices.

26

Reports in Pakistan indicated a 240% hike in

import duties on mobile phones,

27

while in

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

13

Zimbabwe, the Ministry of Finance proposed

a USD 50 levy for the registration of imported

handsets onto a mobile network in addition to

a 25% import tax on mobile handsets.

28

Other

countries have large sector-specific tax rates

and excise duties, including Tanzania, which

charges excise duties on mobile services of

17% of revenue. The sector-specific tax rate

on mobile devices was 18%.

29

Collectively,

taxes and device import duties translate into

high costs of devices which act as a barrier to

smartphone access.

Studies by the OECD and ITU have raised

questions about whether taxes targeting the

digital sector may have adverse distributional

consequences and may dampen the

spillover benefits that the adoption of digital

technologies creates for the entire economy.

30

Other costs affecting handset affordability

Photo credit: ©Asian Development Bank

The total costs of owning a smartphone or

general mobile phone extend beyond solely

the retail price. In the 2017 GSMA report,

additional costs identified include SIM cost,

credit cost, and battery charging costs.

However, the extent to which these costs are

barriers to smartphone access differs across

countries. SIM card costs appear not to be of

concern for participants in Colombia, DRC,

and Indonesia but were reported as a major

barrier in Turkey. At the same time, credit

costs appeared as a moderately universal

barrier in the surveyed countries and one

that disproportionately affects more women.

Niger and Kenya had the most respondents

indicating that cost of battery charging was a

barrier, and likely due to the limited battery

charging infrastructure in those countries.

These additional costs often result in individuals

selecting feature phones, which cost less and

have a reputation of longer battery life and

durability.

31

Unregulated markets

Due to the high cost of smartphones,

distribution channels unauthorized by device

manufacturers have emerged. These are

referred to as parallel or black markets. Devices

sold in these markets are often produced from

components copied from original devices,

resulting in inferior quality devices.

32

Usually,

parallel import flourishes in markets with high

import duties. Markets with high duties tend

to be very inefficient as the duties reduce legal

import significantly, and illegal import then

spikes with the cost and quality issues. Parallel

markets are often used as routes to sell illegally

imported devices, i.e., devices imported

without paying appropriate duties and taxes. In

Nepal, the government’s introduction of a 5%

excise duty on smartphone imports reduced

the legally imported devices while at the same

time fuelling a growth in the black markets for

devices.

33

There are several issues associated with

purchasing smartphones from parallel markets

that can act as barriers to smartphone access.

Most devices purchased from parallel markets

are produced from copied parts that often fail

after a short time in use.

34

Further, these devices

are sold with no warranties or repair options.

35

The non-durability of devices purchased from

parallel markets, the lack of warranties, the

limited repair options, and the risk of phone

data being stolen through invasive software

contribute to the negative perceptions towards

smartphones, thereby acting as a barrier to

smartphone access.

36

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 2

14

2�1�2 Supply-side barrier – last-mile

supply chain issues

Another barrier to smartphone access is last-

mile supply issues resulting from the challenges

faced by smartphone retailers serving remote

communities and the difficulties they face

making their products visible to populations

in such communities. Rural areas are difficult

to access, making transport and logistics costs

significant.

37

Furthermore, there are fewer

retailers of smartphones in rural areas, which

limits options for customers, limits competition,

and complicates the regulation of retail prices.

38

Most device retailers perceive demand in

remote communities to be low due to poor

mobile networks, resulting in fewer retailers in

these communities. In addition to low demand,

remote locations, especially in LMICs, lack

facilities, such as retail space, where mobile

phone retailers can operate, requiring them to

construct their own units. This further increases

the required initial capital outlay to serve the

remote locations.

Hard-to-reach remote communities are also

often off-grid, which means, apart from the

challenge of accessing devices, individuals

also worry about their ability to recharge their

devices. This issue is compounded by the high

costs of battery charging.

39

Literature highlights

the importance of access to electricity

towards digital inclusion. Studies report that

“households without access to electricity,

on-grid or off-grid, need to rely on more

expensive sources of energy to power their

mobile handsets.

40

Therefore, last-mile supply

chain challenges facing smartphone retailers

and electricity supply companies contribute as

barriers to smartphone access and ownership.

2�1�3 Supply-side barrier – foreign

currency availability and exchange rate

volatility

Lack of access to hard currency and exchange

rate volatility represent other commonly

cited barriers to obtaining smartphones.

For example, in Ethiopia, where device

manufacturer Transsion operates, the currency

allocation rules prioritize sectors such as

pharmaceuticals, which limits the foreign

currency available for procuring devices and

device components.

41

In addition, the fact

that most devices are imported necessarily

means that fluctuations in foreign exchange

rates, especially currency depreciation, present

additional challenges to entities seeking to

market devices in LMICs.

2�2 Demand-side barriers

Demand-side barriers are constraints that

individuals face when trying to obtain

access to devices. The 2017 GSMA report

suggests that demand-side barriers can be

classified into main categories such as lack

of consumer understanding and information,

lack of consumer incentives to own and use

smartphones, digital literacy, social and cultural

norms, and issues of security and harassment

for smartphone owners.

2�2�1 Demand-side barrier – lack

of consumer understanding and

information

Finding a balance between the price of

smartphones and the perceived value from

quality is a concern for consumers in multiple

LMICs.

42

However, consumers often have

an exaggerated understanding of the cost

of smartphones. This is compounded by a

misconception that entry-level smartphones

break easily or are of poor quality, leading

consumers to believe that higher-end premium

smartphone models are more desirable.

43

Refurbished devices are becoming increasingly

common, with the goal of creating a more

“circular economy”. However, consumers

remain concerned that refurbished phones

may have short lifespans.

44

This could cause

scepticism over the quality of these devices and

act as a barrier to device uptake.

In most LMICs, and particularly in rural

communities, potential customers lack the

traditional credit history retailers need to

assess credit worthiness for instalment plans.

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

15

In addition to the above, people in the lowest

quintile of socioeconomic status (who tend to

live disproportionately in rural areas) cannot

raise the upfront costs required to purchase

a device. Thus, they become excluded from

accessing smartphones.

2�2�2 Demand-side barrier – lack of

sufficient incentives

McKinsey and Co. suggests that another barrier

to smartphone access is a lack of incentives.

45

This includes “a lack of awareness of the

Internet or use cases that create value for the

offline user” and “a lack of relevant (that is,

local or localized) content and services.” This

barrier is especially common among people

in the lowest quintile of socioeconomic status

(who tend to live disproportionately in rural

areas). As an example, prior to the COVID-19

pandemic, most services were accessible

in person. However, COVID-19 restrictions

resulted in some services being accessible only

online, which incentivized individuals to acquire

Internet-enabled devices like smartphones.

46

The lack of perceived relevance and necessity

of smartphones, coupled with concerns

over device cost, remain barriers despite the

pandemic.

47

2�2�3 Demand-side barrier – digital

illiteracy

Photo credit: ©Asian Development Bank

Another demand-side barrier to smartphone

access is a lack of basic literacy and digital

skills. Digital skills, categorized into low-level,

medium-level, and advanced skills, often

determine the extent of the benefits that

smartphone ownership offers individuals.

Literature indicates that a lack of digital

skills acts as a barrier for adoption and use

of smartphones by instilling fear of using

smartphones and the Internet, which delays

adoption.

48

Studies show that technical and

financial literacy contribute to consumer

confidence in owning and using smartphones

in these emerging markets.

49

Inequalities in education, in some instances

prompted by social and cultural norms, are

major contributors to gender gaps in digital

illiteracy. In low- and middle-income countries,

women are less likely than men to have mobile

phone access and are less likely to be Internet

literate. This is particularly the case among

those who have low income and basic literacy

levels, live in rural areas, or are disabled.

50

Digital literacy thus determines whether users

can achieve meaningful outcomes and make

beneficial use of smartphones. AI-based voice

assistants (such as Google Assistant and Apple

Siri) can also help people who lack digital

literacy to use the Internet by speaking directly

to their smartphones. For example, a farmer

could ask “what will the weather be tomorrow”

and students could ask any question relating

to their education. Voice assistants depend on

widespread adoption of 4G and 5G services.

2�2�4 Demand-side barrier – social and

cultural norms

Research has long established the impacts

of social and cultural norms on device access

across different communities.

51

A study on

mobile Internet use in Bangladesh and Ghana

highlights that women’s use of the mobile

Internet is likely to be impacted more by social

norms than men’s use.

52

Even though this study

focused on mobile Internet use, the findings

echo those of the study on smartphone

ownership conducted by GSMA Connected

Women, which shows that women are 18%

less likely than men to own a smartphone. In

addition, women in LMICs are 16% less likely to

use the mobile Internet.

53

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

Section 2

16

In countries with stringent social norms,

women’s access to and use of devices are often

limited, as women in such societies often lack

financial autonomy. In addition, social and

cultural norms also dictate acceptable use of

smartphones by women. For example, too

much use of smartphones by women can be

associated with wasting time (that could be

used for other chores), immoral activities, and

illicit extra-marital affairs.

54

Another dimension of social and cultural norms

that affects women’s access to smartphone

devices is discouraging women’s uptake and

use of technologies. Research conducted

at the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor

(CGAP) indicates that the lack of confidence in

how to use technology is adversely affecting

smartphone uptake.

55

Further, when family

members (or even members of the society)

are uncomfortable with one member owning

or using a smartphone, this discomfort acts as

another potential cultural barrier. This can be

particularly challenging for women, but it often

applies to any consumer relying on their family

for funds to purchase or access smartphones.

56

2�2�5 Demand-side barrier – security

and harassment

Security and harassment are usually

encountered after an individual acquires a

smartphone. In most LMICs, device purchases

are significant investments. At the same time,

device theft is prevalent, with thousands of

devices being stolen each day.

57

The situation is

further complicated by the lack of and high cost

of device insurance options in most LMICs.

In addition to the negative financial

consequences associated with device loss,

Deloitte indicates that device theft also exposes

personal private information, including

contacts, email addresses, and payments

details.

58

Lower-end devices are also vulnerable to

damage. Participants in the focus group

convened by the International Trade Center

report that the average lifespan of such devices

may be as short as six months.

Some consumers in LMICs share safety

concerns of using smartphones and the

Internet. Mobile devices have the potential to

make owners feel safer by acting as immediate

channels for contact, as well as offering safety

apps, mobile money, and other services.

However, this is a benefit cited more by male

mobile owners than female mobile owners due

to the online harassment and lack of awareness

for mobile-related safety features and apps of

women.

59

Furthermore, reports by GSMA identified

concerns over online harassment and the

potential for misuse of personal images and

data as barriers, contributing to consumer

perceptions of safety.

60

Some consumers in

Latin American countries cite security threats

as a reason for not owning a mobile phone

much more often as a top barrier than any

other region. At least 16% of men and 13% of

women who do not own a mobile phone in

Guatemala share concerns of physical safety as

a main barrier for phone ownership.

61

Personal

safety, unwanted contact with strangers, and

information security remain large barriers to

mobile phone ownership.

62

Strategies Towards Universal Smartphone Access

17

1

GSMA: The state of mobile Internet connectivity 2021.

2

Chen: A demand-side view of mobile Internet adoption in the Global South.

3

World Economic Forum: Internet for all: A framework for accelerating Internet access and adoption; World

Bank: World development report 2021; GSMA: The mobile gender gap report 2021.

4

Pew Research Centre: Smartphone ownership is growing rapidly around the world, but not always equally.

5

Connecting Africa: MTN Is launching a $20 smartphone.

6

Chen: A demand-side view of mobile Internet adoption in the Global South.

7

Chen: A demand-side view of mobile Internet adoption in the Global South.

8

GSMA: Accelerating affordable smartphone ownership in emerging markets.

9

World Bank: Digital financial services.

10

Chen: A demand-side view of mobile Internet adoption in the Global South.

11

ITU: Connect2Recover: A methodology for identifying connectivity gaps and strengthening resilience in the

new normal.

12

World Bank: Digital financial services.

13

GSMA: Accelerating affordable smartphone ownership in emerging markets.

14

A4AI: Affordability Report 2021.

15

GSMA Connected Women: The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021.

16

Klapper: Mobile phones are key to economic development.

17

GSMA: Accelerating affordable smartphone ownership in emerging markets.

18

A4AI: Affordability Report 2021.

19

Sun and Grimes: China’s increasing participation in ICT’s global value chain: A firm level analysis; Wajsman

and Burgos: The economic cost of IPR infringement in the smartphones sector.

20

James: Extending the experience to Sub-Saharan Africa.

21

Business Today: Smartphone prices jumped 27% since COVID began in 2020: IDC.

22

Tech Crunch: Global smartphones hit lowest since pandemic start.

23

Mint: Smartphone, TV prices may rise amid covid resurgence.

24

GSMA: Rethinking mobile taxation to improve connectivity.

25

Business Daily: New 10pc phone tax takes effect Friday.